Cello Thumbposition in the Neck Region

Placing the thumb up on the fingerboard changes our hand’s posture and alignment greatly. These changes are particularly disadvantageous in the Neck Region because of the larger distances between the notes (compared to in the higher registers). Those larger distances create a lot of extra tension for the fingers and hand, which is why thumbposition in the Neck Region is normally quite unergonomic, strained and uncomfortable. In the neck region, vibrato, expressive playing and extensions all tend to become much more difficult as soon as we put the thumb up on the fingerboard. This is why we almost never use the thumbposition to finger passages with a singing, lyrical, melodic character in the Neck Region.

There are however two very important exceptions to this general rule of “thumbposition in neck region = tension”:

- the perfect fourth interval between the thumb and third finger, and

- the major third interval between the thumb and second finger.

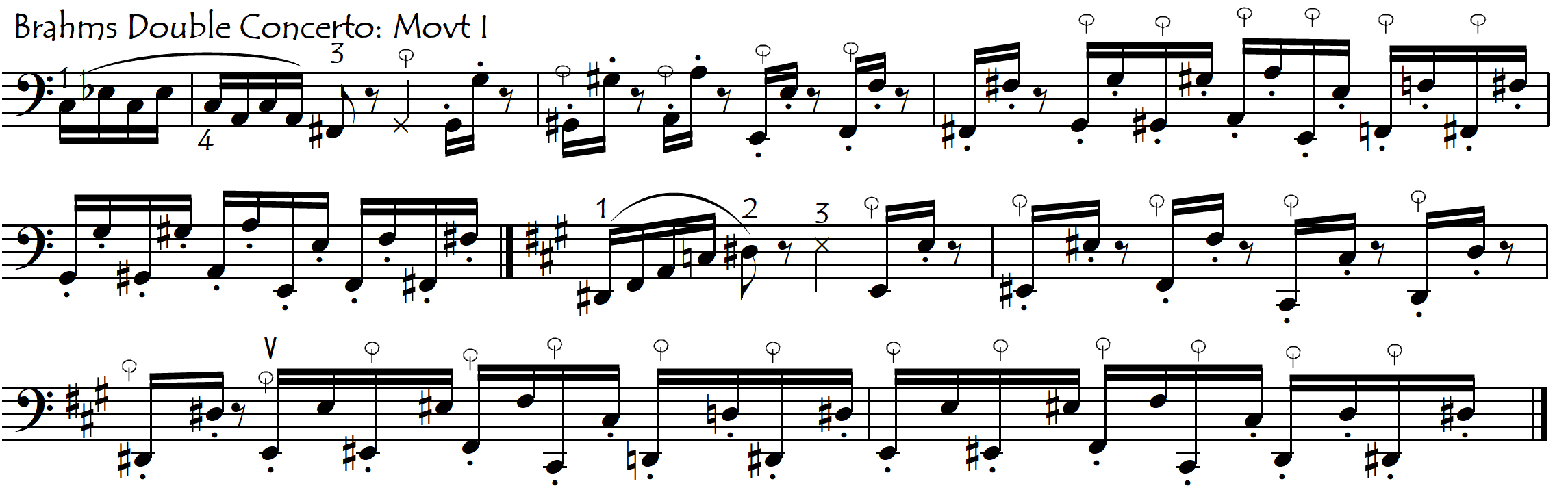

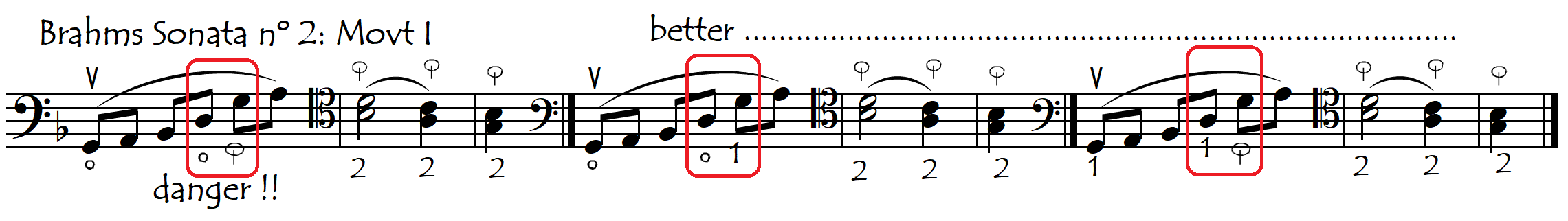

Playing either of these intervals (on the same string or across strings) with the thumb and the corresponding finger is normally much less tense than playing them with the 1-4 extended (or double-extended) position. Using the thumb in the Neck Region for these intervals avoids the need for the 1-4 extended position and therefore actually allows our hand to be more relaxed than the standard 1X4 and 1XX4 fingerings, thus facilitating a nice loose vibrato. And the smaller our hand is, the greater the reduction in tension level will be by using the thumb instead of the 1-4 extension. Compare the following two repertoire passages, all of which contain some major-third hand stretches. They are presented with two fingering choices: firstly with a “standard” fingering and then with a fingering using the thumb. In these examples, the reduction in hand tension due to the use of the thumb may (or may not) compensate for the greater intonation difficulties that we usually have with the doublestopped shifting on the thumb.:

In the above examples, we looked at the possible advantages of using the thumb as the lower finger for major third intervals. For the perfect fourth interval (and octaves to the higher string) in the Neck Region, the advantages of using the thumb are even clearer as here our use of the thumb avoids the 1XX4 double-extension (and not just the simple major third 1X4 extension). For the small-handed cellist, passages that move around the Neck Region in octaves will almost always be easier with the use of the thumb than with the 1XX4 double extension (or the alternative leaps across three strings).

Exactly the same advantages apply to our standard artificial harmonics (in which we also require the same perfect fourth spacing between our bottom and top fingers).

Unlike octaves and major thirds, however, other simple intervals between the fingers – especially 1-3 minor thirds and 2-3 wholetones – can become quite uncomfortable (if not impossible) in thumbposition in the Neck Region. This is why we can consider the use of the thumb in the Neck Region as only being for “special occasions”, such as:

- to play octaves, artificial harmonics and some double-stopped passages in thirds

- to help us out in faster passages (these don’t normally need vibrato) in which the use of the thumb is a way to avoid awkward shifts, double-extensions, fifths, and/or string-crossings

- to avoid other uncomfortable stretches (especially in doublestops).

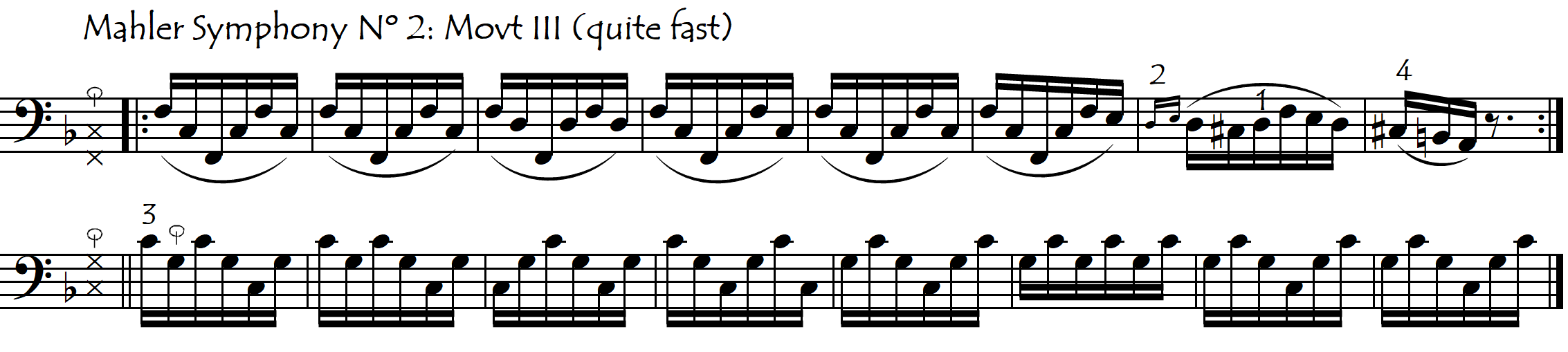

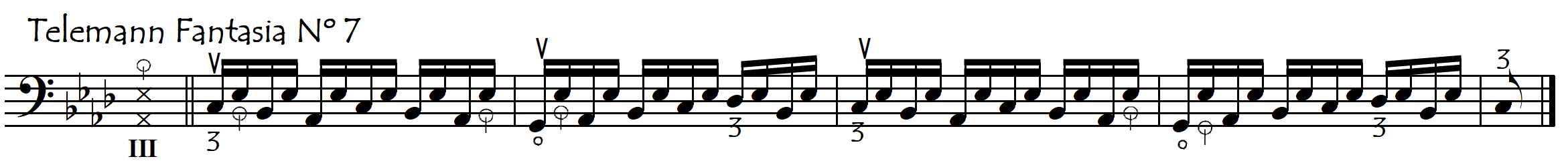

It is quite surprising just how often these “special occasions” arrive. In exotic keys, in which we cannot use the open strings, difficult faster passages can suddenly become very simple if we use the thumbposition:

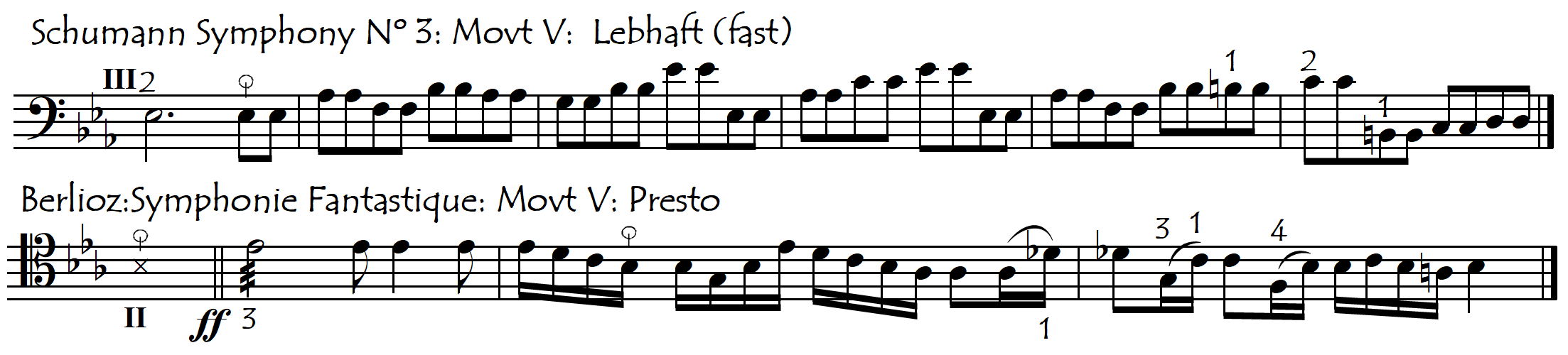

Even in the Classical Period symphonic repertoire and in very simple keys, the use of the thumb in the Neck Region – although not at all authentic (see History Of Thumb Position) – can often make a fast awkward passage suddenly much easier, as in the following example.

In the above passages, the benefit of the use of the thumb is mainly to avoid the fast shifting, but in other passages – in music of every epoch – thumb use can totally eliminate the complications caused by fifths and/or string crossings/stretches.

With its potential to reduce the number of shifts, string crossings and extensions, as well as to greatly simplify the playing of fifths, the use of thumbposition in the neck region – especially for very fast passages – can often give us a much simpler fingering solutions than “standard” fingerings :

But even in not-very-fast passages, the use of the thumbposition can greatly reduce hand tension that would otherwise be caused by fifths and slurred octaves:

Sometimes we can even use the thumb to solve an awkward Neck Position passage ……. but not in the original low Neck Region ! By moving the passage onto the next lower string(s) we bring it a fifth higher up the fingerboard, thus bringing it into a zone where the distances between the fingers are much smaller, thus making our use of the thumbposition now much more comfortable.

Here, the use of the thumb eliminates, instantaneously and simultaneously, the need for extensions, position changes, and awkward fast jumps across three strings for the bow.

Sometimes however we may not want (or be able) to play the passage on the lower strings in a position a fifth higher. In these cases, to avoid the very uncomfortably strained wholetone interval between the first and second fingers in the lowest fingerboard positions we may want to use the third finger on the major third interval above the thumb thus using T13 instead of T1x2:

The small-handed cellist might even do this in passages that also need the third finger, giving rise to some very non-standard, bizarre fingerings. The following excerpt is from the “Allegro” 2nd movement of Telemann’s Fantasia for Unaccompanied Violin Nº 1:

This example also makes use of another “trick” that we may need very occasionally in thumbposition in the neck region: the tipping of the thumb towards the higher string in order to be able to play the lower open string without removing the thumb from the fingerboard. This allows a rapid alternation between the thumb and the lower open string which can be very useful at times (see below for more discussion about the thumb and the open strings).

THE PROBLEM OF THE CRUSHED FIRST FINGER

The use of the higher fingers on the lower string will, when using thumbposition in the Neck Region, often oblige our first finger to stop the higher string in the “crushed”, tightly-curled position in which it presses on the string from the side, horizontally. This is only useful (practical) in faster passages in which we don’t need vibrato on that first-finger note:

THE PROBLEM OF THUMB PLACEMENT AND REMOVAL

Apart from the discomfort of the large finger spacings, one of the main difficulties of using the thumb in the Neck Region comes from the radical posture change that the hand and wrist undergo when we place the thumb on (or remove it off) the fingerboard in this region. The obligatory posture change that results from placing the thumb up on the fingerboard is much greater (and therefore more disruptive) in the Neck Region than in the higher fingerboard regions. And because the posture change is so radical, we also need more time to comfortably get our thumb up onto the fingerboard in the Neck Region than we do in the higher regions. For this reason, if we can place our thumb up on the fingerboard before the passage starts, then we eliminate a rather large problem, and our comfort and security will normally be greatly enhanced. In all the cellofun editions, a notehead in form of an x indicates the silent, preparatory placement of a finger on the string. Here, “silent” means only that the note is not sounded with the bow: we will normally check the pitch of these preparatory notes with a discreet lefthand pizzicato (see Lefthand Positional Sense).

At other times, however, we do not have the luxury of being able to prepare our thumb during a silence and have no choice but to place it on the fingerboard while we are playing. This is a bit like trying to get dressed while walking – it makes it all much more complex. In these situations, the importance of thinking ahead and consciously releasing the thumb from its contact behind the cello neck as early as possible cannot be overestimated. This will often be the key to our successful use of the thumb in the Neck Region.

In the above excerpt, we are lucky in that our thumb can be brought up at a moment when the hand is one, steady “position” (meaning that we are not doing a shift ). The following link opens study material (exercises) for working on this skill.

Thumb Placement On The Fingerboard In Neck Region In One Hand Position (No Shifts): EXERCISES

Sometimes however we need to bring our thumb up while the hand is shifting (almost always to the thumb).

This complicates matters significantly and constitutes the next level of difficulty. Once again, consciously placing the thumb up on the fingerboard as early as possible (even before the shift starts) will help make this potentially tricky task feel natural and comfortable. The following link opens study material (exercises) for working on this specific skill:

Thumb Placement On The Fingerboard In Neck Region During Shifts: EXERCISES

Sometimes we have so little time in which to put the thumb up on the fingerboard that we may find it easier to simply forget about trying to get the thumb up and just play the passage in the neck position, in spite of the fifths, double extensions and other difficulties which the thumb would have solved:

THUMBPOSITION AND THE OPEN STRINGS: INCOMPATIBILITY AND DANGER

When playing in thumbposition, if we remove the thumb and all fingers completely from the fingerboard then we are suddenly deprived of all lefthand contact with the fingerboard. This is the equivalent of being lost in space: we now have no anchor and no positional reference (see The Contact Principle). Likewise, and for the same reason, placing the thumb up on the fingerboard after an open string is a very unstable and insecure fingering option. These are very dangerous situations which we will avoid at all costs.

In both cases, the reason for our total loss of contact with the fingerboard is because of the need to play an open string. In the higher regions of the fingerboard, the open strings are a long way from the pitches that we are playing and are unlikely to be needed, but when playing in thumbposition in the neck region, the open strings are right there amongst the pitches that we are playing and there is a much greater likelihood of disturbance and incompatibility. Playing open strings in normal neck position does not cause any positional insecurity because the thumb, tucked away behind the neck, maintains permanent contact with the cello, acting thus as our anchor and permanent positional reference.

NECKREGION THUMB AND PRE-ROMANTIC VIOLIN TRANSCRIPTIONS

Beethoven and Schumann were pianists and their compositions can be quite unidiomatic (difficult to finger and bow) for all string players. Mozart, Bach, Schubert and Telemann however also played the violin/viola and their writing for these instruments is usually very idiomatic: not only did they understand the characteristics of the instruments but also probably played their pieces themselves. Unfortunately, none of these composers played the cello, which is probably one of the reasons why they wrote so little for the cello as a solo instrument, so if we love to play their music – and not just the accompaniments and bass lines – then we will have to steal it from their violin/viola repertoire.

When we transcribe violin/viola music for the cello, we soon discover that we will need to use a lot of thumbposition in order to be able the play the huge number of fast passages that are conceived for the violin (with all the notes of the scale under the violinist’s hand in any one position). Using thumbposition in the higher fingerboard regions is not a problem for us – we are used to that – but if we transpose pre-romantic violin music down a fifth then we will often be in the neck region, where the frequent requirement for thumbposition can feel at first quite unusual and uncomfortable.

BACH AND THE NECKREGION THUMB

Bach never took his cello writing into the Thumb Region. In fact, Bach and his cellists were not aware of the possibilities of thumbposition anywhere on the fingerboard. So how then could cellists of his time have played this passage from the Prelude of his Third Suite? (see Thumb History and Bach and the Thumb for the answer). This passage is a very good example of the utility of the thumb in the Neck Region as a means to avoiding difficult (or impossible) extensions:

************************************************************************************************

The following link opens up a large compilation of repertoire excerpts for which the use of thumbposition in the neck region is either an absolute necessity or, at a minimum, a definite fingering possibility.