Fast Coordination: The Importance of the Beat

This page is part of the larger subject of Fast and/or Tricky Passages: Speed and Coordination

THE BEAT AS A COORDINATION AID

When the movements of both hands coincide with the beat, this gives us a very powerful coordination aid, but when we displace the beat then our coordination problems multiply exponentially.

In both of the above examples, our mechanical movements are absolutely identical. The only difference between them is the displacement of the beat by one semiquaver (16th note). But this simple, tiny rhythmic displacement makes an enormous difference to the difficulty (and to the interest) of the passage. The fact that our note changes (left hand) and string crossings (bowhand) come on the beat in the first example makes these bars much easier to play than the right side example (in which our changes must be made off the beats). This shows us that it is easier to coordinate rapid movements when they are synchronized with the pulse. Here below is another example of the same principle:

In the following example, once again, the notes are exactly the same in both examples and only the rhythmic pulse changes. The displaced (second) version of this example is slightly easier to coordinate than the above ones because here at least we have a “meeting” of the beat with the note change on every barline :

Now let’s try placing accents on the first note of every beat (or every alternate beat). In the left side examples it becomes clearly easier to stay coordinated if we do these accents. This is because, in these examples, the finger changes and the string crossings coincide with the pulse, so accenting the beat helps us coordinate these movements with it. In fast passages where major changes coincide with the beat, practicing with accents on the beat can be a good way to practice the passage. But these accents, while helping us technically (to coordinate the two hands) can also become an anti-musical trap in a musical situation in which maybe that particular passage doesn’t want accents.

Putting accents on the beat in the right-side (displaced beat) examples is a very interesting experiment. Do the accents help us here, as in the left-side examples? Whereas they do help the bow and the rhythm (we will feel this especially when we play the example without the left hand), the accents on the beat disturb the left hand. This is because the left-hand movements (finger articulations) in these examples do not coincide with the beat and are in fact syncopated. In fact, these passages can be considered as “broken syncopations” in which the left hand is syncopated but the bow isn’t. What the left-hand does in those “beat-displaced” examples is shown here below:

Putting accents on the beats in these three examples would be disturbing. We would never do that unless the composer especially asked for it, and we would certainly never use accents on the beat as a rhythm and coordination aid in a fast syncopated passage. That would have the opposite effect to the desired syncopation effect and would be an instant recipe for getting “tangled up” and out of time. In fact, in order to help our rhythm and coordination in syncopated passages we tend to do exactly the contrary: we bring out the syncopation by accenting the offbeat changes slightly. This is why the above examples are actually easier to play as written above (with bow changes on each note change) than they would be if they were all slurred: the bow changes give us the little accents, coinciding with the finger changes, that help us stay coordinated.

All of this leads us to think that it may be easier to play these “displaced-beat” examples if we in fact think of them as syncopated, and thus accent slightly the note-changes. In the case of example 2 above, this would means however that we will be giving accents not only off (between) the beats but also always to our up bows. Would it not perhaps be easier to start with an up bow in order to have all the accents on the down bows ? This is an interesting question: let’s try it both ways (with a metronome of course):

But is it worth playing the entire passage with “unnatural” upbows on every beat Doesn’t that create more problems than it solves? See below for a discussion about the importance (or not) of the pulse with respect to the bow direction.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE TWO HANDS: WHICH HAND IS OFF THE BEAT?

In passages in which we are playing “off the beat” it can be interesting to see exactly which hand is off the beat. Sometimes both hands move off the beat, but at other times only one hand moves off the beat while the other stays “on the beat”.

In the first variation of these examples, both hands move on the beat. In the second variation, the lefthand moves on the beat while the righthand moves off the beat. In the third, it is the lefthand that moves off the beat while the bow moves on the beat. In the last variation, both hands are moving together, off the beat, which may actually be easier to coordinate than the middle two variations in which the hands don’t coincide.

The movements that we do that might or might not coincide with the beat are:

- for the left hand: finger articulations, releases and, shifts

- for the right hand: bowchanges and string crossings

Now let’s look in isolation at these different elements with respect to the coordination/beat equation. We will start with the left hand:

THE LEFT HAND AND THE BEAT

ONLY LEFTHAND ARTICULATION (ON ONE STRING AND IN ONE POSITION)

We can examine lefthand articulation coordination/beat problems in isolation by playing any passage (or note sequence) that uses only one string and one position (in other words, without shifts or string crossings) such as in the following repertoire example:

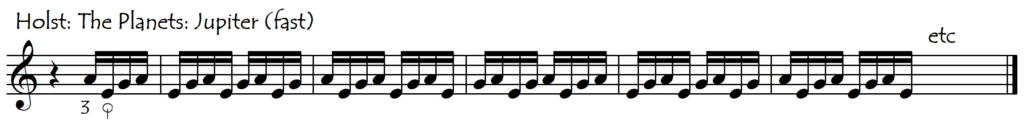

This excerpt illustrates a typical beat/coordination problem that arises because a triplet “cell” is played in a quadruplet rhythm. If this exact same note sequence was played in triplet time it would be considered a simple, uncomplicated passage because the beats would coincide always with the same note of the pattern.

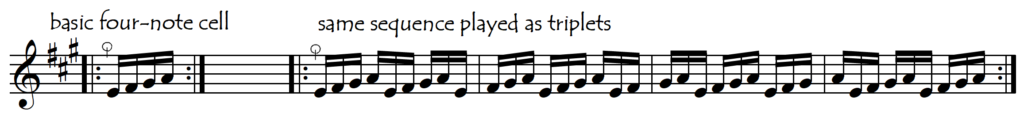

We can reproduce this situation in its inverse by taking a basic four-note “cell” and playing it in compound (ternary) rhythm.

The difficulties of these passages are purely “brain” problems: there are no mechanical problems at all. These difficulties are due to the fact that we think both in beats and in “note clusters” and when the rhythmic pattern of the cluster doesn’t coincide with the beat pattern then we can get in a tangle. It is a little like trying to put a square peg in a round hole or rubbing circles on our chest while tapping our head. The greater the power and speed of our brain’s processor, and the more deeply relaxed we are, the easier these problems will be to overcome. See at the bottom of the page for a greater discussion about these 12=3 x 4 = 4 x 3 brain/body teasers.

SHIFTING AND THE BEAT

Shifting on the beat gives us a coordination advantage, but also creates the risk that we might put unwanted accents on those beats. Sometimes we will prefer to shift on the beat even though the fingering ergonomy may be worse (for example because the need for extensions).

If there are clear accents in the passage (even if the accents are just the normal beats) then we will make it easy for ourselves if our shifts can coincide with those accents.

Try also the following excerpt in which the final two bars are presented in the two opposite ways: first, it is fingered with the shifts to the accents, and secondly with the shifts just after the accents. Which is easier?

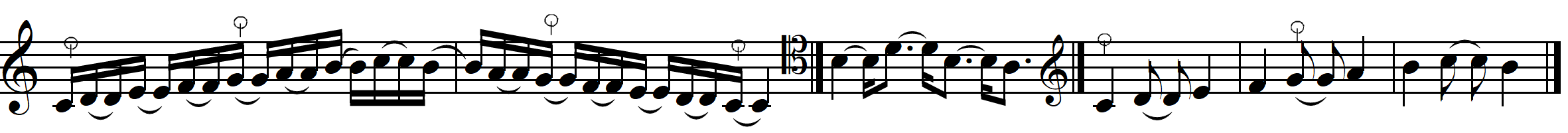

The second movement of Elgar’s Cello Concerto gives us a lot of very good material for the study of fast coordination with a displaced beat because its main thematic material has the unifying characteristic of the note changes being displaced to one semiquaver after the beat:

THE BEAT AND THE BOW

We need to look at two aspects of the relationship between our bowings and the beat:

- the relationship between bow direction (up or downbows) and the beat in separate-bow passages, and

- the relationship between slurs and the beat in passages with slurs

THE DOWNBOW ON THE BEAT

When our note-changes coincide with the beats this helps us to coordinate them and play them with ease. In the above Elgar example, the complication with respect to the beat is caused by the dislocation of the note movements: the notes change “off” the beat (or, in other words, “between” the beats). Another type of complication with respect to the beat is when our downbows don’t coincide with the beats (pulse). In fast/tricky passages, having a new downbow coincide with a beat can be considered the optimum situation for helping to reduce our coordination problems to a minimum as we will probably see when we try the above examples starting on upbows.

We won’t talk here about why this is, but it certainly feels most natural for string players to have the pulse (the accented beat) on the down bow, especially when we are playing many fast “small” notes. We will leave for later the question of whether this is just habit or whether there is a biological, ergonomic basis for this difference.

Unfortunately, this ideal situation of having downbows on the beat does not always occur, and very often we will need to do the contrary: have an upbow on the beat. This subject is looked at in detail on the page dedicated to “Reverse Bowings“.

SLURS AND THE BEAT

In the above excerpt, all the note changes and string crossings occur on the beats. The only aspect of our playing that is “off the beat are our slurs (bow changes). We can invent exercises like this to work on our bowchange/beat coordination in an efficient isolated way.

MIXED LEFTHAND AND RIGHTHAND BEAT/COORDINATION PROBLEMS

Sometimes we will be lucky enough to find a passage in which all of the major changes for both hands (changes of string, bow direction and shifts) fall on the beat: in these situations our coordination problems are at their lowest level of complexity. We sometimes also have the possibility to choose our bowings and fingerings for a passage in such a way as to make all the main changes fall on the beats. This may involve fingering the same scale differently in the upwards direction than downwards to make all the changes fall on the beat in both directions. Below are two examples of this. The following link opens a page with more of these types of exercises in which all the major changes fall on the beats:

More often than not however we can’t do this and will just have to practice our complex passages (with large movements off the beat) enough that those problems of coordination with the beat no longer disturb us. But then, having learnt the passage with one rhythmic structure, perhaps we will need also to relearn it with the beat displaced. This is hard work for the brain. In the following two repertoire excerpts, the left and right hands do exactly the same thing in each excerpt with the only difference being the displacement of the beat. Fortunately here the music is displaced by an entire triplet, which is less disruptive than a displacement of 1,2, 4 or 5 quavers would be.

A SPECIAL CASE OF BEAT DISPLACEMENT: 12 = 3 X 4 …… BUT ALSO 12 = 4 X 3

Relatively frequently, composers will play with the fact that twelve notes can be regrouped either as four groups of three notes or as three groups of four notes. This gives rise to some tricky situations which we could consider either as problems of “cross-rhythms” or as problems of “doing things off the beat”. The most common situation occurs in 3/4 bars where three groups of four semiquavers (16th notes) are regrouped as four groups of three notes:

The equivalent trick can be done “in reverse” with 12/16 (or 12/8) time signatures, in which four groups of triplets are regrouped as three groups of four notes:

The following link opens up several pages of exercises in which we explore the different varieties of this “12 = 3 x 4 or 4 x 3” situation:

Coordination and The Beat: 12 = 4 x 3 or 3 x 4: EXERCISES

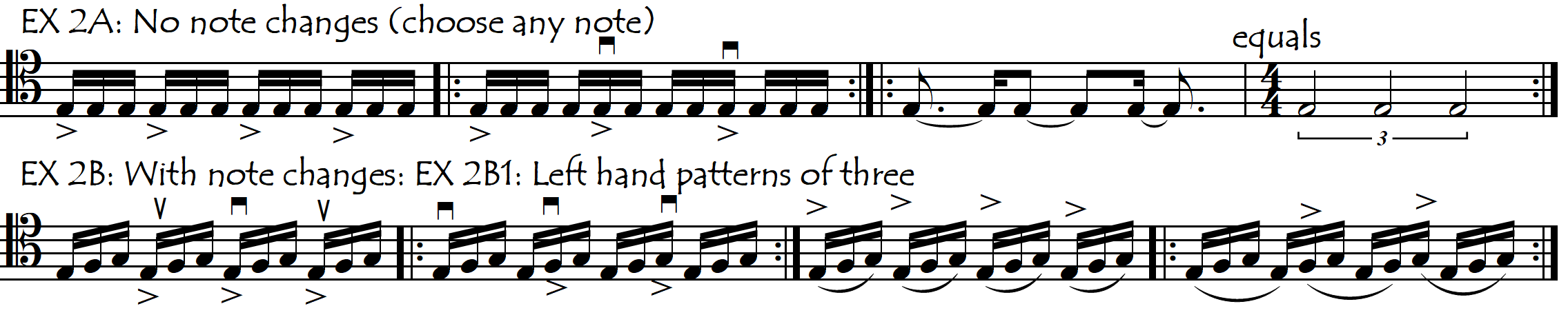

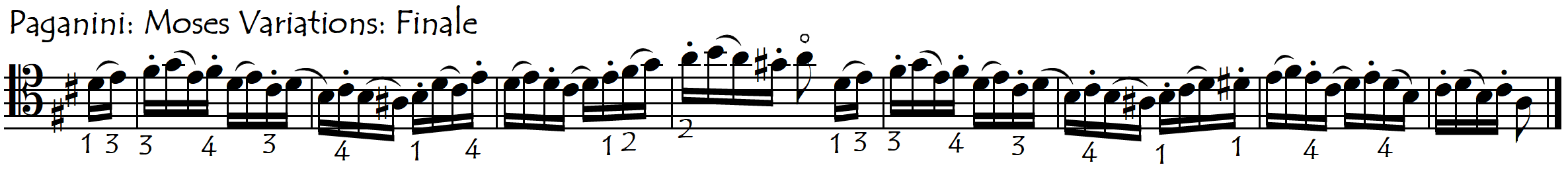

Subdividing a 12/8 bar into three groups of four, or subdividing a ternary bar into four groups of three, is complex, but at least we coincide with the beat on each barline. This makes each barline like a home-base reference. But what about the following example from Paganini’s “Moses” Variations ???

Here, not only do we need to regroup quadruplets into groups of three but also those groups of three notes have a tricky asymmetric bowing, and because our time signature is 2/4 we have no respite at the barlines. This is perhaps one of the most difficult examples of this type of rhythmical/coordination test. It doesn’t get much trickier than this. In the following example, we create a pedagogical progression to work our way up to playing Paganini’s original bowing. We can start with the bottom line, which is simply the notes without any bowing and articulation coordination complications. Our next step will be the middle line, a compromise “intermediate” stage in which we now group (slur) the notes in groups of three. The final stage is the top line: Paganini’s original “coordination challenge”.

CONCLUSION

The following link opens up a curiosity in which standard scales are fingered and bowed in such a way as to make all the main movements (shifts, string crossings and bow changes) coincide always with the beat. In order to achieve this coinciding of the main bodily movements with the beat, we need to change the fingerings of identical note sequences according to where the beat lies in the sequence.

Moving Always On The Beat: EXERCISES

To work on the coordination skills required for doing movements “off the beat” we can practice simple scales and arpeggios, played at gradually increasing speeds (always with a metronome) with different varieties of “dislocated” rhythms and reverse bowings as in the following examples.

We can then add different slurs, and can also play with the accents (placing them either on the beats or on the finger changes). It is very interesting to join the “broken syncopations” of the left hand by converting the bowing also to syncopated. This of course doesn’t change the left hand movements in any way, it just makes it easier to see what is happening and makes it easier to coordinate the two hands. The following example shows the first of the above exercises, played with a series of different bowings/articulations, in order of increasing complexity of coordination. We can treat the other exercises (those in in 3/4 and 6/8) in exactly the same way.

Click on the following links for more material for working on similar coordination problems derived from playing (moving) “off the beat”.