Dotted Rhythms

Dotted rhythms are a curious phenomenon from several different points of view: technical, musical, mathematical, ………… and perhaps even philosophical. What then is the significance of dotted rhythms in the musical language? Which bowings are best and why? Why are they considered “French Style”? Are they always “French Style”? Are there different degrees of dottedness (dottiness)? But we had better start with the ultimate and most basic question: what is a dotted rhythm?

To skip these theoretical discussions and go directly to some practice material, click here:

Study Material for Practicing Dotted Rhythms

DEFINITION OF A DOTTED RHYTHM?

If we try and count how many dotted rhythms there are in a certain piece or movement, we quickly realise that, unfortunately, the definition of what is (and what isn’t) a dotted rhythm is not as simple as we may have initially thought. Let’s start by looking at what is definitely not a dotted rhythm.

WHAT IS NOT A DOTTED RHYTHM

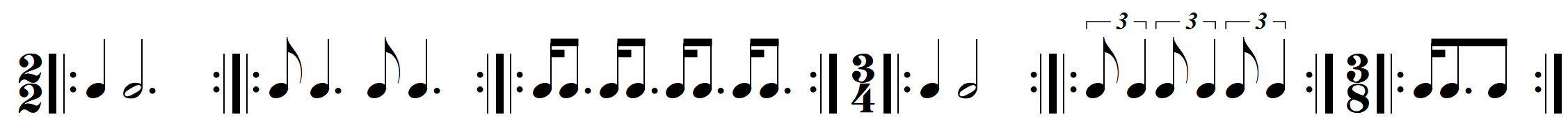

When each pulse of a mini-group of binary or triplet pulses has a newly articulated note on it, then the group is “undotted”.

In the above examples, we could replace any note with its full semiquaver (16th note) subdivision without changing the “un-dotted” nature of the figures. This means that any half-note can be replaced by eight 16th notes, any quarter-note by four 16th notes, and any eighth-note by two 16th notes.

WHAT IS A DOTTED RHYTHM

Prolonging a note over the next pulse in the group, so that we are taken across to the following pulse without a new articulation, is what leads us into the new and wonderful worlds of both dotted rhythms and syncopations.

The above examples are classic, unambiguous dotted rhythms, but the following variants ….. ???

Here we might have a doubt about whether these really are “dotted rhythms” but in fact, these examples are the same as those just above them, with the only difference being that our “short note” has been subdivided into two.

And what about the following examples ? The first example is dotted only for the left hand, the second example is dotted only for the bow’s string crossings. Are these “dotted rhythms”?

REVERSE DOTTED RHYTHMS

We tend to think of a dotted rhythm as having a small note tucked onto the end of a large note, a little bit like a child following an adult. This is definitely the most common form of dotted rhythms, but sometimes the roles are reversed and it is the child who leads the adult:

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A DOTTED RHYTHM AND A DOTTED BOWING

A dotted rhythm doesn’t necessarily mean a dotted (articulated) bowing. We can have a dotted rhythm in the left hand combined with a totally legato bowstroke:

CREATION OF (SOMEWHAT DILUTED) DOTTED EFFECTS BY THE BOWING EVEN WHEN NOTE VALUES ARE NOT DOTTED

A dotted effect does not have to be purely rhythmic: it can also be created in a passage of constant equal (undotted) rhythmic values by a combination of the asymmetrical melodic line contours reinforced by our bowings (articulations).

CREATION OF VERY DILUTED DOTTED EFFECTS EXCLUSIVELY BY THE MELODIC LINE

In the above example, the melodic line contours were reinforced by our asymmetrical bowing, and the combination of these two mutually reinforcing factors contributed to the creation of the notable dotted effect. An even more diluted dotted rhythm effect occurs when the melodic pattern (contours) of totally undotted notes is played without the reinforcement of the asymmetrical bowings. Even with totally undotted, symmetrical bowings, the melodic line alone can still create a somewhat dotted effect:

DIFFERENT DEGREES OF DOTTINESS

From all the above we can see that a dotted rhythm is not a binary, either-or affair: there are different degrees of dottedness. This concept will be looked at in greater detail further down the page.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF DOTTED RHYTHMS IN MUSICAL LANGUAGE

The dotted micro-units of two notes (or three notes in compound time) are asymmetrical, lopsided, and unbalanced. Undotted rhythms can be compared to normal walking or running: the pace can be fast or slow but the rhythm of the steps is regular and metronomic. In other words, each step is equidistant from the one before it, each step coincides with a rhythmic pulse, and no pulses are “missing”. In contrast to this, dotted rhythms are the equivalent of skipping, dancing, or (in extreme cases) of Monty Python’s “Silly Walks”.

The simple fact of adding the dot gives a new and instantaneous vigour and interest to the note progression: suddenly the rhythm comes alive. Dotted rhythms add interest, expression and tension/release to music. The particular tension and release patterns inherent in dotted rhythms have parallels in human movement as mentioned above: adding the dot is what we do when we change from running to skipping, from walking to lilting, and from marching to dancing.

Undotted rhythms are more mechanical, regular, steady and serious. When we are working hard, we are often “undotted” (participating in a race, or doing “serious” training, for example). When we are fooling around, literally “playing” (or dancing) we are often more dotted. Our english word “dotty” – normally meaning a sort of charming, silly, harmless craziness or eccentricity – is also often a good description of the effect of dotted rhythms. The dot usually gives music more character, most often making it more graceful, playful and delightful. To illustrate this influence of the dot, try playing Fred Wilson’s Hornpipe (Irish folk music) to children, firstly without, and then with the dotted rhythm. Normally they will squeal with laughter and delight with the dotted version!

Another great little piece which explores the effect of adding dots to a “straight” tune is Chandler’s Hornpipe, with its two undotted and two dotted variations.

At the beginning of Stravinsky’s Pulcinella ballet music (on which our Suite Italienne is based), the opening theme comes twice. Each appearance is identical, except for one “tiny” dot that is “missing” in the first presentation. Let’s compare the characters of the two forms:

Once again, “what a difference a dot makes”! The dot is what makes this melody truly italian: lively, playful, frisky etc. It seems inconceivable that the young neopolitan Pergolesi could have written this theme without that second dot: it’s just too “square” sounding. But it is easily conceivable that the dot could have been lost accidentally during the process of transcription or editing. Certainly, Piatagorsky would seem to have been in agreement with this idea because in the cello transcription that he made with Stravinsky of this piece (Suite Italienne) the theme is dotted both times, unlike in the violin transcription.

At slower speeds, dotted rhythms can give a mannered, courtly, lilting, even teasing character. This is especially so when we wait – to great effect – till the absolute last moment, before playing the short note (see “double-dotting” below). The Allemande from Bach’s 5th Cello Suite illustrates well this type of dotted rhythm. At faster speeds, dotted rhythms usually give a skipping, rollicking, sparkling, sprightly, crisp, playful, dancing character. The first movement of Schubert’s Piano Trio nº 1 in Bb is full of examples of this type of dotted rhythm.

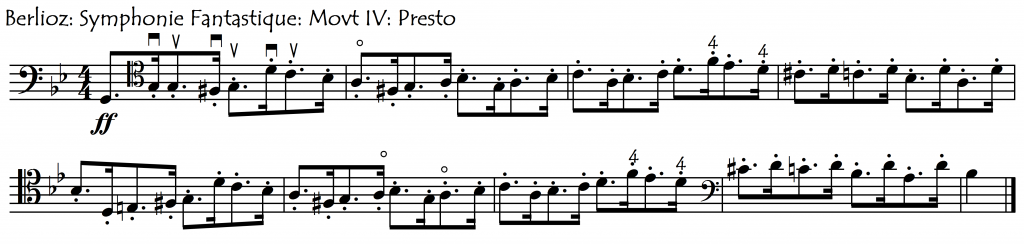

In all of these above cases, the effect of the dotted rhythm is lightening and delightful, but it is not always like that. If we don’t relax the pressure on the long note, then rather than creating a lilting alternation of tension and release, the effect of the dot can be to actually augment the tension. Playing dotted rhythms in this way, especially at faster speeds, loudly, and when the dotted pattern repeats itself relentlessly, can create great intensity. We can find many examples of this in the driving, intense music of Beethoven, such as in the first movements of both his 7th Symphony and his Quartet in f minor Opus 95. This use of the “intense dot” can be taken even further, to create maniacal, sinister and violent effects such as in the following example by Berlioz:

“FRENCH STYLE” VERSUS “GERMANIC STYLE”: DOTTED VERSUS UNDOTTED

With the exception of the ultra-intense “Beethovenian” dot mentioned above, dotted rhythms tend to lighten the music, independently of whether the movements are fast or slow. The frequent use of dotted rhythms, especially in Baroque music, is considered “French Style” because of the character it gives to the music: sprightly, capricious, flirting, lightfooted or nervous, impetuous, and excitable. When Paul Tortelier used to take his little trade-mark skip up onto the soloist podium, we could also call this an excellent example of a “French dot”. Undotted rhythms on the other hand, at any speed, have a more steady, predictable character. They can be slow and stately, or sprinting and driven, but are usually more “serious” and therefore referred to (in Baroque music) as “Germanic Style”.

Look at the following table and you can see why Bach’s Fifth Cello Suite is considered to be in the “French Style”. It has more dotted rhythms than all the other suites combined !

|

FREQUENCY OF DOTTED RHYTHMS IN THE BACH CELLO SUITES |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SUITE |

SUITE |

SUITE |

SUITE |

SUITE |

SUITE |

|

|

PRELUDE

|

0 |

10 (16) |

0 |

3 (6) |

Prelude 44 (52) Fugue 2 |

0 |

|

ALLEMANDE |

18 |

14 |

3 |

0 (1) |

78 (82) |

33 (45) |

|

COURANTE |

3 |

2 (6) |

0 (4) |

0 (2) |

34 |

0 |

|

SARABANDE |

7 (9) |

4 (19) |

10 |

43 (44) |

0 |

31 (43) |

|

GALANTERIE I |

0 (2) |

0 (1) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

GALANTERIE 2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

GIGUE |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

63 |

0 |

|

TOTAL |

28 |

30 |

13 |

46 |

221 |

64 |

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, when we try and count exactly how many dotted rhythms there are in a certain piece or movement, we quickly realise that, unfortunately, the definition of what is (and what isn’t) a dotted rhythm is not actually completely precise. This is why in the above table some numbers are in brackets (these numbers include the “doubtful dots”). See below for more discussion about this subject.

In Bach’s Partitas and Sonatas for Solo Violin, several of the movements also stand out for being extremely dotted: the first movements of the B minor Partita and the C major Sonata each have more than 100 dotted-rhythm figures.

FRENCH STYLE: THE “DOUBLE-DOT”

What really gives a strong “French style” however is when we decide to “double dot” these dotted rhythms. This is optional, but was in the Baroque period perhaps an automatically assumed way of playing these rhythms, in the same way that we nowadays automatically (hopefully) play “swing” music syncopated, even though it is traditionally written out “square”. Thus, in some Baroque music, we can choose between playing in the German style (as written) or in the French double-dotted style in which the semiquavers (16th notes) are played late and as semidemiquavers (32nd notes) as in the following examples taken from Bach’s Fifth Suite.

Actually, this “double dot” is often not what it says it is. Rather than playing the short note twice as short as written, we often make a compromise which converts the semiquaver (16th note) into a triplet semiquaver (a 24th note?) rather than the ultra-short semidemiquaver (32nd note).

For more examples of this “double dotting” see the article about Bach Cello Suite Nº 5, and especially the discussion about the Gigue of this suite. Also, Fritz Kreisler’s “Liebesleid” plays around a lot with the differences between double and normal dotting and is a very enjoyable way to experiment with this effect. The following link opens up a page of these and other repertoire examples using double-dotting:

Double-dotted Rhythms: REPERTOIRE EXAMPLES

DEGREE OF DOTTEDNESS

Let’s explore this subject some more now. Not only can there be a certain ambiguity as to whether or not a rhythm is dotted, but also an unambiguously dotted rhythm can be more or less intensely dotted (as with the French style double-dotting above). Also, any particular musical passage can have a greater or lesser frequency of dotted figures within it. Let’s look now in greater detail at the questions of:

- how dotted is any particular dotted figure?

- how dotted is any particular passage?

HOW DOTTED IS ANY PARTICULAR DOTTED FIGURE ?

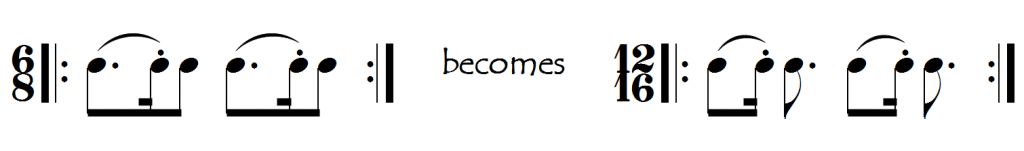

The degree of dottedness of any particular dotted figure depends on the degree of shortness of the short note in relation to the lengths of the long notes. The greater this difference, the more intense will be the “dottedness” of the rhythm as the following examples will show. When we “doubledot” we halve the length of the short note, which has the effect of “doubling” the dottedness. In these examples, we progress from only very slightly dotted to extremely dotted. Each of the two rows of music below uses identical rhythms, just notated differently. The numbers beneath these two examples show the relative lengths of the long and short notes.

We could also make one single number to show the relation (ratio) between the length of the short note and that of the entire dotted figure. For the above progression, this would give the following numbers. The first number is the length of the short note while the second number is the total length of the dotted figure (short note + long note):

1/2.5 1/3 1/4 1/6 1/8 1/12 1/16

Triplet dotted rhythm figures (𝅘𝅥 𝅘𝅥𝅮) are more relaxed (less intensely dotted) than quadruplet (𝅘𝅥. 𝅘𝅥𝅮) figures and we have to be careful in a lot of classical music (in contrast to pop, swing, jazz etc) to “not let our quads become tripe”. Or, in other words, to keep our dotted rhythms crisp and tight (quadrupletised), not letting them relax into laid-back triplets. A piece of music that we could use in order to work on this potential problem is the Courante from Bach’s D minor Partita for solo violin, in which the alternation of triplet quavers with dotted quaver/semiquaver figures is constant.

HOW DOTTED IS ANY PARTICULAR PASSAGE ?

Apart from the degree of dottedness of any particular dotted figure, we can also look at how dotted is any particular passage. This is determined by the frequency of the dotted figures within the passage.

TECHNICAL PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED WITH DOTTED RHYTHMS

For the left hand, all fast dotted passages, whether legato or non-legato require special attention to be given to their fingerings in order to plan as much as possible for the major changes in both left and right hands to occur after the long notes rather than after the short notes. These fingering problems are looked at on the following page:

Fingering Dotted-Rhythm Passages

For the right hand, non-legato dotted rhythms, especially when they are fast and repeating, can present us with significant bowing problems (see Bow Division) because of their asymmetry. Let’s look now at these bowing problems:

BOW DIVISION IN NON-SLURRED DOTTED RHYTHMS

1: TWO-NOTE DOTTED FIGURES: RETAKES, HOOKS AND HAMMERS

Because of their unsymmetrical nature, finding a good bowing for duplet (not compound-time) dotted rhythm passages requires a little thought.

If we try to play any extended passage of repeated duplet dotted rhythms simply “as it comes” (using a new bow for each note), we will find two things happening involuntarily:

- our bow will be rapidly propelled to the frog or to the tip and/or

- we will find ourselves giving unwanted accents on the short notes in order to try and avoid the above effect

These two problems occur because we are moving our bow for much longer in one direction (usually in the down-bow direction) than in the other reverse direction (usually the upbow direction). Under these conditions, it is extremely difficult to stay in the same part of the bow because the maths simply does not add up (balance out): it is as though we were taking several steps forward for each one step backwards, while all the time trying to stay in the same place.

Using low bow speed + high bow pressure on the long notes, and then high bow speed + low pressure on the short notes is the instinctive way to minimise these problems of asymmetry but there are other alternatives that require however a little more planning and intelligence: the “retake” and the “hook”. Let’s look now at these two components of our bowing toolbox:

1:1 THE RETAKE

If we have time to lift our bow off the string before (or after) the short note, then this allows us to retake the bow (bring it back in the air to where we want it) and we can do the bowing “as it comes” without any problems of bow division.

This important subject has its own dedicated page:

1:2 THE HOOK

If we don’t have time to lift our bow off the string to retake then we will need another solution for the bow division problems created by the asymmetry of repeated dotted duplet rhythms (figures). The most common alternative to the retake is “hooked” bowings in which the little note is played in the same bow direction as the long note that precedes it. With hooked bowings, each pair of dotted figures neutralises each other with respect to bow displacement, and the net effect on the bow position is zero: in other words, we automatically and naturally stay in the same part of the bow. It is as though we were taking three steps forward then another step forward, followed by three steps back followed by another step back.

Hooked bowings are traditionally notated by a slur and a dot, but this can be ambiguous sometimes (for example when the short note is connected [legato] to the following note, or in inverted dotted rhythms). To avoid this ambiguity we could also use a dashed-slur to better indicate hooked bowings and it is this .

“Hooked bowings” is a large and important subject which has its own dedicated page:

1.3 HAMMERED COUPLES

A special bowing case for dotted duplet figures is the ricochet “hammered” bowing that we use sometimes to give the crispest ultra-percussive dotted rhythms. Whereas a “hooked” bowing would allow the” long” notes to actually sound longer, the hammered ricochet bowing keeps all the notes equally short. There is nothing graceful or playful about a dotted rhythm when played in this manner!

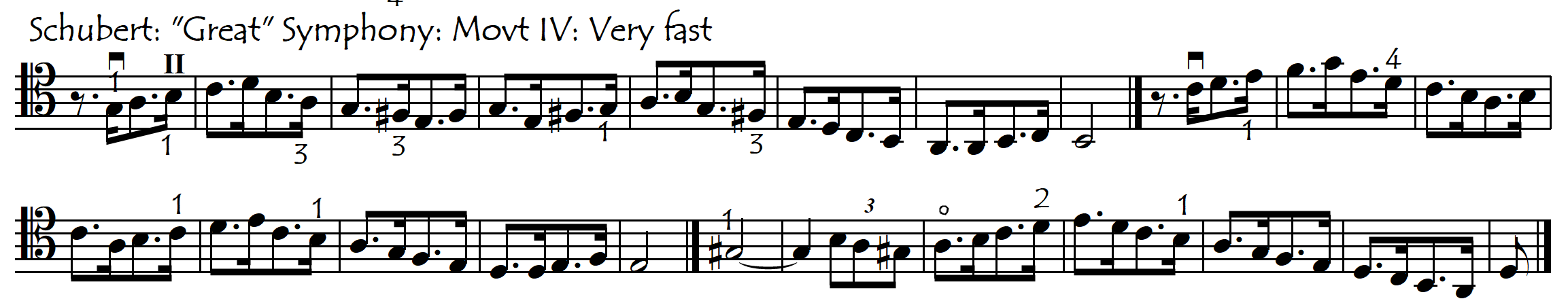

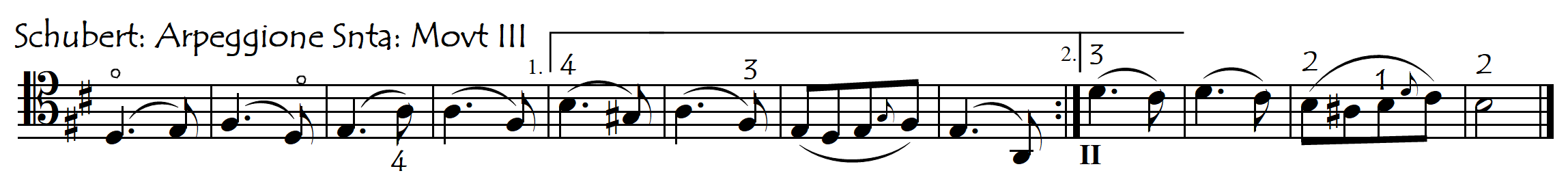

While this type of bowing is mainly used in very loud passages, it can also be used in ultra-crisp, tight, high-energy soft passages that go so fast that they become unplayable, or at least unreliable, with our standard hooked bowings. In the following example we might use this “tight” bowing even though Schubert writes the music in a more “laid-back” compound-time (6/8 instead of 2/4):

These may seem like “backwards” bowings: don’t we normally play our short up-beats on an up-bow? Well yes, we do …….. but only when the note after the short upbeat needs to be played longer. In very fast dotted-rhythm passages in which both up and down beats need to be short, these “backwards bowings” allow us to get into an effortless, self-sustaining bow loop, in which the wrist is making its favourite anti-clockwise circles (which is what helps the bow to bounce effortlessly- see Spiccato). Try the same passages (or the same rhythm on any series of notes) with the opposite bowing and you will see how it suddenly becomes very hard work. Suddenly we are fighting against the natural tendencies of the bow. Now it no longer wants to bounce and, what’s more, it now wants to take us out away from the frog. Curiously, André Navarra, (and even today, some other cellists with similar personality characteristics) preferred these heavy, “hard-work-bowings”.

2: THREE-NOTE DOTTED FIGURES

The three-note (usually in compound-time) dotted rhythm figure, however, has exactly the opposite characteristics to the two-note version. When played “as it comes” the bow doesn’t gradually work its way out to one end. This is because each pair of figures has a neutral effect on the bow’s position, and thus the bow comes back automatically to where it started. When we do these figures with hooked bowings however we are taking always several steps in one direction for only one step in the other so it is here, unlike with the duplet hooked bowing, that we are entering into unbalanced territory and need to be careful not to give unwanted accents on the last note of each figure.

When played with the hooked bowing and at high speed, the compound dotted figure can easily mutate into an unwanted duplet version

To avoid this mutation, we can either make the supreme effort to play the short note always as late as possible or we can play the bowing “as it comes”.

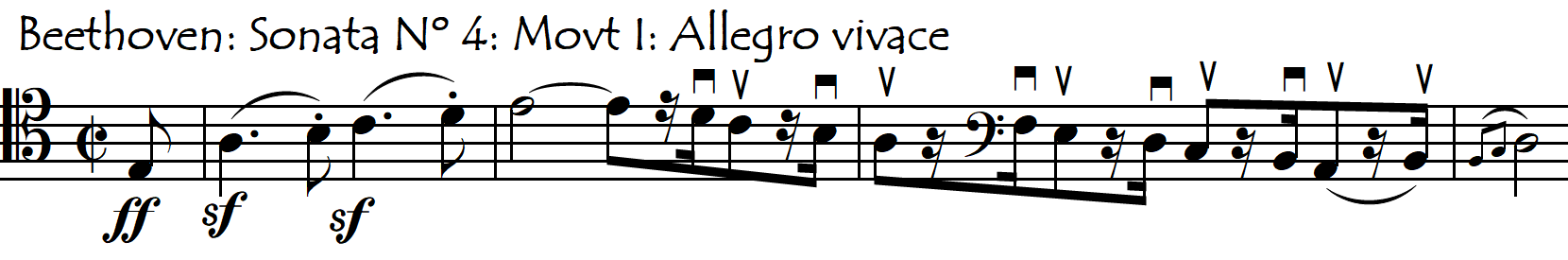

The “Allegro” of the first movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony provides lots of excellent practice material for dotted compound rhythms because this little rhythmic motif appears in almost 80% of its bars (measures), which is why the cello part can be used as a sort of study: just play it with a metronome and then with a full orchestral recording. In the combination of the cello part with the other orchestral voices, every possible configuration of this rhythmic motif can be found.

RIGHT-HAND PRACTICE TIP FOR FAST DOTTED RHYTHMS

It can be helpful to practice fast dotted rhythm passages without their “short notes”. This helps us to reinforce the basic bowing and rhythm of the “main notes” and to keep the little ones “little”.

HOW FAST IS TOO FAST FOR DOTTED RHYTHMS ?

The most intense, concentrated, dotted passages are those in which we have endlessly repeating, tight quadruplet dotted figures (not compound time or triplet) at top speed. We can do them either hooked or with our “backwards” down-up bowings (as in the Berlioz and Schubert examples above).