Pitch For Cellists (Ear Training)

This article about “pitch” could also be called “ear training” or “aural training”. On this page we will look uniquely at the pitch aspects of ear training. For a discussion of the rhythmic aspects of aural training click on the highlighted link. Specific pitch-reading problems derived from inappropriate notation are dealt with on the following dedicated page:

Pitch: Reading and Notation Problems

Normally (but not always – see Music Reading Problems), music starts in our imagination – in our inner ear – and only then is transferred onto an instrument, voice or paper. All musicians require a highly developed “inner ear”, capable of imagining different pitches and different intervals. This “ear training is a huge part of the intellectual skills that are necessary to become a competent musician, and this is especially so for string players. With no frets, keys or valves to help us to know where we are on the fingerboard, we are often almost as dependent on our aural skills as singers are.

In the lower regions of the cello fingerboard (and in general on many other instruments), we often don’t need to imagine in advance, the pitch of the note that we want to sound because we know physically/mechanically where the finger needs to go in order to play that pitch. This is very bad for our ear training !! One of the best ways to develop our aural pitch skills is by singing, and probably the most convenient and most relevant things to sing are our cello parts. Being able to sing our cello parts is a very useful fundamental musical skill. It will show us which intervals we have trouble imagining and greatly develops our pitching skills, thus helping both our cello-playing and our music-reading. This skill is especially necessary in the higher fingerboard region because up there in the stratosphere, unlike in the lower (Neck and Intermediate) regions, we have no visual or mechanical references to help us to know where each note is on the fingerboard (see Positional Sense). In the Thumb Region, if we can’t imagine the pitch of the note before we play it then we will be literally “lost in space”.

Therefore, it is especially for shifting in the Thumb Region – and most especially for larger shifts up into this region – that we usually need to have a very clear idea of the pitch of our target note, before the shift, in order to be able to do the shift with security. In other words, we need to be able to “hear” (imagine) the arrival note (or the “Intermediate Note” in the case of Assisted Shifts) with our inner ear before we start the shift. This requires good aural skills (ear training). For most shifts in (and into) thumbposition we must find the notes almost exactly like a singer: “by ear” (with no concrete physical external reference points to help us).

Our hand can find notes in relation to physical, muscular (kinesthetic) and visual reference points but, unless we have perfect pitch, our inner ear will always find a note in relation to another previously-sounded note. Therefore the basic element of all ear training with regard to pitch is the musical interval: semitones, tones, thirds, fourths etc. We can imagine these intervals both vertically (harmonically, one note on top of the other at the same time) or horizontally (one note after the other).

HORIZONTAL AND VERTICAL HEARING

Unlike keyboard instruments, most of our time at the cello is spent playing “melodically” (or “horizontally”) in the sense that we are usually playing only one note at a time, just like singers and wind/brass players. Only when we play doublestops or chords do we actually need to imagine intervals “vertically”, hearing them simultaneously with our inner ear rather than sequentially.

In one way, our monophonic (one-voice) lines make our job easier because we only need to hear/imagine pitches one at a time. But in another way, this monophonic ear makes our job harder because, without the benefit of the “harmonic” ear, we are obliged to calculate each interval with reference only to the previous note rather than with reference also to the notes in the harmony underneath. Those harmonies can greatly help us to know to which pitch we are going. To say the same thing with other words, having a better-developed “vertical/harmonic” aural sense would help us greatly with our horizontal/melodic pitch sense. We will start our discussion with the “melodic” ear before progressing to the “harmonic” ear.

GETTING FAMILIAR WITH MELODIC (LINEAR, HORIZONTAL) INTERVALS: SIGHT-SINGING OR FINGERING?

String players can survive with a less developed inner ear than singers because – thanks to our four strings and five fingers – many of our large and/or strange intervals can be calculated as simple (and small) fingering distances without any need to hear the actual sounding interval in our heads. For singers, it is as though they play everything with only one finger and on one string. To sing the following example we would need to calculate (hear in our imagination) the diminished fifth and then the major seventh which is quite difficult. To play it on the cello, however, the only interval we really need to calculate is the minor third up the D-string from Bb to Db, the other intervals being a natural consequence of our finger positions:

It is only when our large intervals are on the same string – and especially when the target note is in the Thumb Region (where we lack spatial references) – that we absolutely need to be able imagine our interval before playing it.

Certain intervals and series of intervals are easy to imagine with our inner ear: octaves, thirds, sixths, perfect fourths and simple scales for example. But others are more difficult, and it is these more complex intervals and patterns that we need to work on specially, not initially at the cello but rather just with our inner ear: singing aloud, or singing silently in our imagination.

Often, to reinforce our aural imagination of any interval, it helps to remember a little catchy tune which uses that particular interval, preferably often. For the perfect fourth, for example, we could use the opening bars of Mozart’s “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (A Little Nightmusic) in which our perfect fourth is repeated six times in a row:

In the following catchy theme from the music to the film “Dr Zhivago” it is the interval of a sixth that is repeated over and over. The five minor sixths of the opening (blue enclosures) are followed by nine major sixths (green).

The above examples deal with some of the most simple intervals but we can use the same “catchy tune” idea for more difficult intervals (see below). To understand (and thus imagine) complex intervals better it can help if we “construct” them from their basic simple component intervals in the same way that understanding complex numbers is made easier if we break them up into their components (758 = [7 x 100] + [5 x 10] +[8 x 1]). For example, a diminished 7th interval is composed of three minor thirds piled on top of each other, while a diminished fifth is composed of two of these minor thirds.

Sometimes, especially for large intervals, rather than building an interval up from its components, it is easier to find it aurally as a simple subtraction or addition from an easily found aural reference point. In the same way that the number 999 is easiest to understand as 1000 minus 1, a major seventh is usually easiest to hear as an octave minus a semitone, and a major 9th as an octave + 1 tone.

We need to become perfectly accustomed to the different manifestations and fingerings of common intervals and interval patterns. The most difficult intervals for us to hear (imagine) are usually difficult either because of their large size or because of their “strangeness” (the most atonal or harmonically radical ones). Even some very common intervals and interval patterns can actually be quite difficult to imagine. Let’s look in more detail at some of these now. Click on the highlighted links for practice material (exercises and repertoire excerpts). We will start with the smallest intervals and work upwards.

SEMITONES: CHROMATIC SCALES

On this page, we are looking at the problems of hearing chromatic scales. The intellectual problems of reading them, and the physical problems of playing them, are dealt with on separate pages.

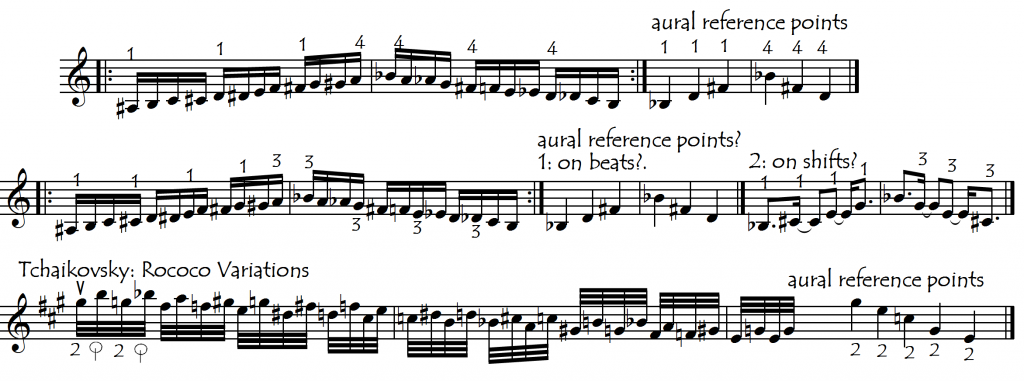

Unless they are played quite slowly, we will not be able to control (imagine) every note of a chromatic scale (see Control – Overcontrol). We need instead to have just a few reference points during the scale. These reference points will be determined almost certainly by the rhythm, and will probably be the notes that fall on the strong beats. Sometimes this makes our job easy, as in triplet rhythms which divide a chromatic scale into a series of minor thirds, giving us the diminished 7th arpeggio:

When however a chromatic scale comes in binary groupings, then the octave is made up of three major thirds (instead of four minor thirds). This is much harder for us to hear with our inner ear, especially when the shifts don’t coincide with the strong beats.

The following link opens up two pages of exercises that will train our ear to hear better (and therefore be better able to control) chromatic scales on the same string(s). In these exercises we use the open strings to check our intonation at various points in the chromatic scales:

Pitch Control Exercises For Chromatic Scales On the Same String: Double-stops

Normal chromatic scales do not pose a reading problem, because we know that every interval is a semitone. Serious reading problems are however posed by irregular chromatic passages because we need to decode each interval separately. Click on the highlighted link for more about this.

“STRANGE” SCALES AND MODES

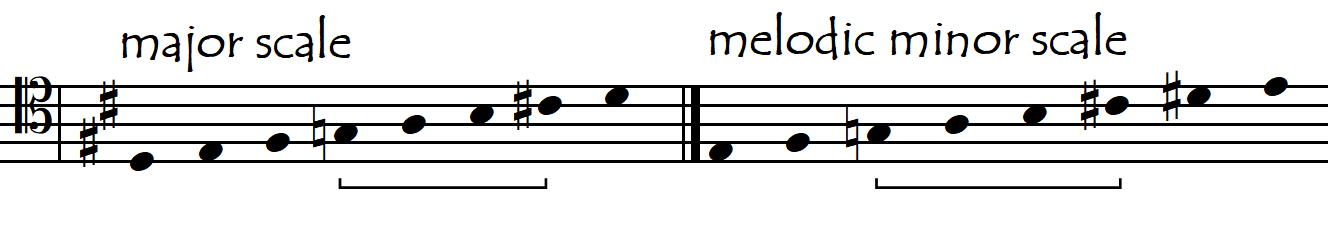

We are normally so used to the major and minor scales that they do not present us with any aural difficulties: we can sing them up and down with absolutely no problems. Other more unusual scales (modes) require more work (practice) to feel familiar. We normally practice/sing our major and minor scales starting on the tonic. If we practice starting them on other notes of the scale then we will be effectively accustoming ourselves to all the different modes.

AUGMENTED SECONDS

One of the most characteristic “unusual” scales/modes, used in a lot of gipsy, jewish and arab-influenced music, features the augmented second interval as a defining element of the musical language. Even though the augmented second is the same distance, measured in semitones, as the minor third, we will hear it differently. Whereas the minor third does not feel any need to resolve, the augmented second definitely wants to resolve (expand) outwards to a major third interval. In western classical music this interval is also a standard feature of “harmonic minor” scales:

THE MINOR THIRD AND DIMINISHED SEVENTH CHORDS

The minor third is normally an easy interval to imagine even in the most difficult harmonic circumstances, and it is often an extremely useful interval with which to break up (subdivide) larger complex intervals. For example, the minor third is the most tonally-useful common denominator of the octave. Whereas an octave divided in half gives two augmented fourths (or diminished fifths) which can be quite hard to imagine with our inner ear, the octave divided into quarters gives four minor thirds, which are very easy to imagine. So in any series of consecutive minor thirds, the fifth one will be the octave of the first one.

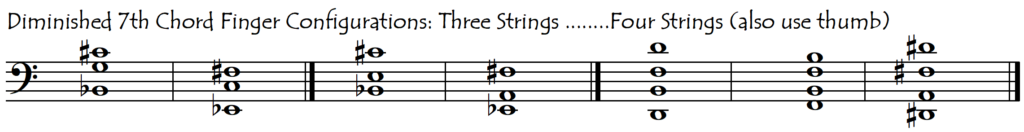

While semitones and tones are the building blocks of all our different scalic progressions, with the minor third we make a quantum leap into the totally new world of harmony. The minor third is a basic harmonic building block, not only of the major and minor chords but also of the important diminished seventh chord, which is composed of minor third intervals piled on top of each other. This chord is both very expressive and extremely versatile: by lowering any one of its notes by a semitone, that new note becomes the bass of a dominant seventh chord, permitting a modulation. This makes it a very popular, much-used harmonic and melodic device, so we really need to have its intervals very well ingrained into our ears. On the cello, we have several possible diminished 7th chord finger configurations across three and four strings. These can be transposed all over the fingerboard, especially if we use the thumb:

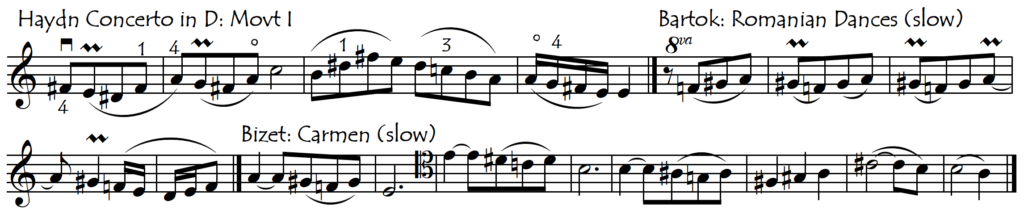

In his Third Symphony, Sibelius writes us a little “study” for the first two of the above finger configurations:

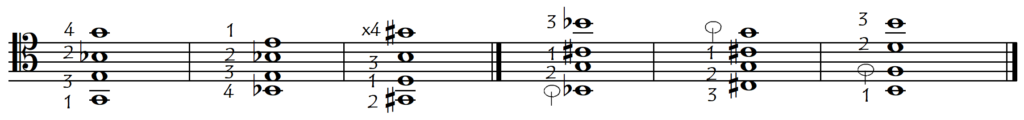

Here below are some of the fingering possibilities for the four-string diminished 7th chords. Some of these finger combinations are much less ergonomic than the 3-string versions:

Here below are links to practice-material featuring these useful and important piles of minor thirds:

Diminished Seventh Arpeggios/Chords: EXERCISES Diminished Seventh Arpeggios/Chords: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

DIMINISHED FOURTHS

This interval is very much a characteristic of minor keys as it is the standard interval between the seventh (leading note) and third notes note of the scale. Even though this interval is “the same” as a major third for the hand, it usually looks bizarre and we have to hear it as “a semitone + a whole tone + another semitone” rather than as two whole tones. Often we can think of (hear) this interval as a minor third, anticipated by a dissonant, passing-note semitone appoggiatura:

PERFECT FOURTHS

This is an “easy” interval because it is so abundant but it still helps sometimes to have a little catchy tune full of perfect fourths to remind us of (and reinforce) our mental picture of this interval:

AUGMENTED FOURTHS/DIMINISHED FIFTHS

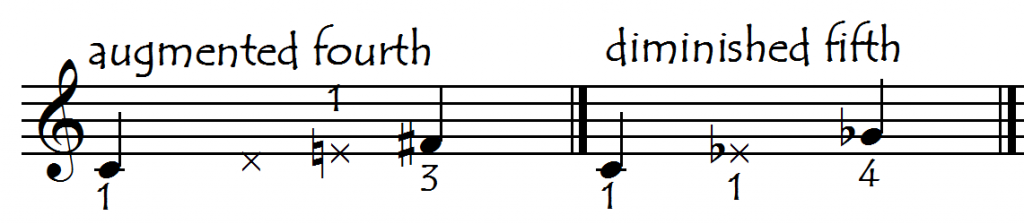

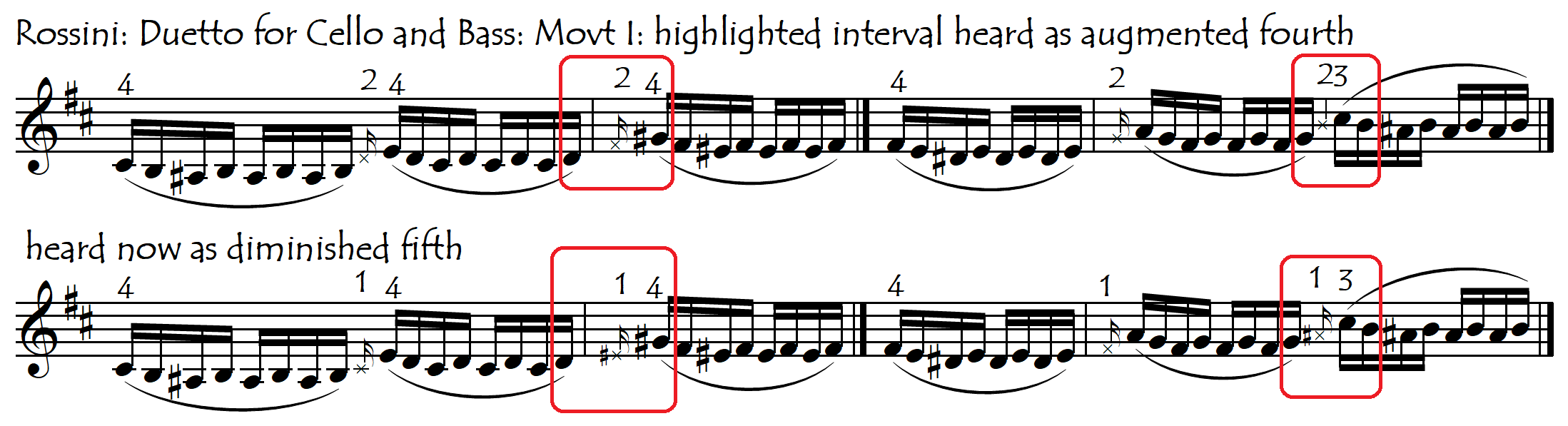

Although these two intervals are exactly the same distance apart, we “hear” them differently, in the sense that the “intermediate notes” (those occurring between the starting and finishing points) are quite different for the two intervals. We will normally hear the diminished 5th as the sum of two minor thirds, whereas to hear the augmented fourth we will probably use the whole tone scale as stepping-stones. Because this augmented fourth interval is made up of three tones, it is also called the “tritone”:

We are very accustomed to diminished fifths because, being part of the diminished seventh chord, they are found very frequently. Augmented fourths however, even though they occur between the fourth and seventh notes of every standard major scale (and between the third and sixth note of any melodic minor scale), are still somewhat unusual as a melodic interval and may cause us more aural (pitching) problems than the diminished fifth.

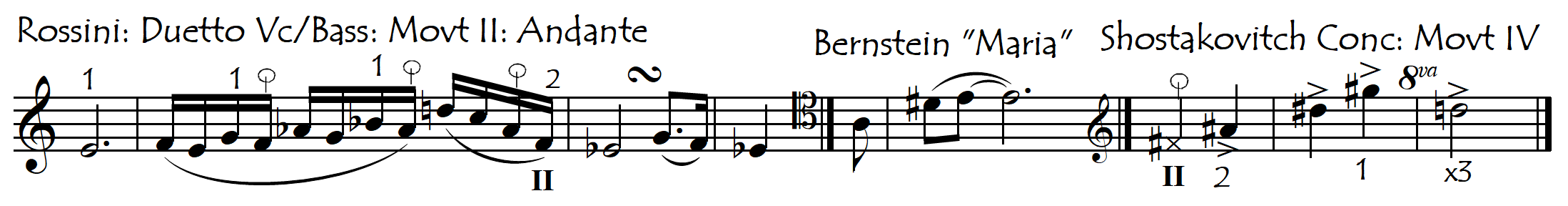

Here are some augmented fourths from the repertoire:

Sometimes we can choose how we want to “hear” the interval: either as a diminished fifth or as a tritone (augmented fourth). This choice may be reflected in our choice of intermediate notes:

The following link opens some practice material (repertoire excerpts and exercises) for working on these intervals at the cello:

Augmented Fourths and Diminished Fifths: EXERCISES AND REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

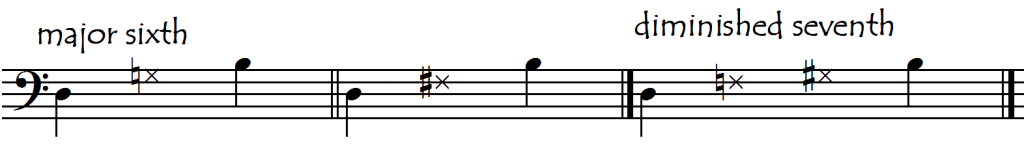

THE DIMINISHED SEVENTH INTERVAL

The diminished seventh interval is a curious one because not only does it sound the same as the major sixth, it is also normally notated identically. So why is it called a diminished seventh? ….. because just like for the above example (the augmented fourth and its identical diminished fifth), we hear the two identical intervals differently. In imagining the major sixth we will use quite different aural stepping-stones to the layered minor thirds that we will use for the diminished seventh.

MINOR SEVENTH INTERVAL (AND DOMINANT SEVENTH ARPEGGIOS)

We can “hear” (find) this interval in two main ways:

- by imagining a note one octave higher, and then going down a tone, or

- by imagining the stepping-stones of the dominant seventh arpeggio (major third + two minor thirds)

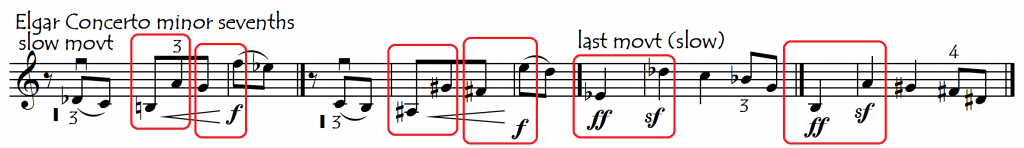

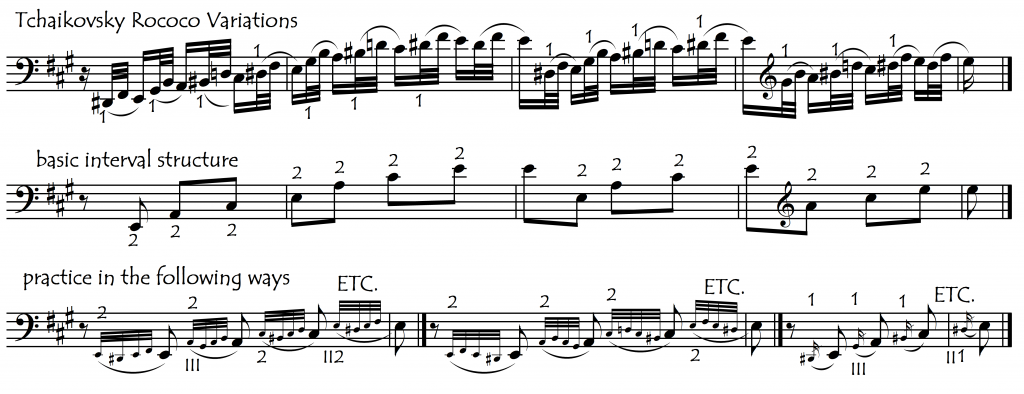

FINDING THE BASIC INTERVALS IN A COMPLEX PASSAGE

Often a quite simple passage can be made to seem more complex than it really is due to the presence of chromatic “ornamentations” which produce some strange (hard-to-sing) intervals. It helps a lot in learning these passages if we can see and practice the underlying basic interval structure.

And here is another repertoire example of this procedure, this time with a diminished 7th chord as the basic structure that we need to hear:

VERTICAL HEARING

HARMONY

Knowledge and awareness of the harmony underneath an awkward interval or passage will usually help us to better hear the interval with our inner ear (and thus find it on the fingerboard). Very often it is only when we can imagine (or hear) the harmonic accompaniment, that the melodic interval will suddenly make musical sense. Our lack of a “harmonic ear” can make the memorizing of chordal passages (also broken chords/leaps) more difficult. These types of passages occur quite commonly in Baroque music:

Here is a page of Baroque repertoire excerpts featuring these same types of passages for which “harmonic hearing” will help us to memorise the pitches of the leaps more easily:

Harmonic Ear: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

COUNTERPOINT AND DOUBLE-STOPS: SEPARATING THE VOICES

For good control and intonation in our doublestopped passages, we need to be able to clearly separate the two voices with our ears. This can be quite difficult at first because we spend so much of our playing time just hearing and tuning one note. In most of our music-making the “other note” is played by another instrument and we don’t have to worry about it because it is beyond our control, but in double-stops, suddenly, we need to control two notes simultaneously. Playing and practising double-stops forces us to develop this aural skill. Perhaps the best way to develop this aural skill quickly and efficiently is to practice singing one of the voices while sounding only the other voice with the cello.

The following link opens up two pages of doublestoppped scales in thirds and sixths which we can use as material for developing this skill. While the left-hand “plays” on both strings, the bow plays only the line that we are not singing. We will probably discover that it is much easier to hear (and sing) the top line of any doublestopped passage and that therefore we may need to spend more time singing its the lower line.

Play One Voice While Singing The Other

THE SINGING CELLIST

Singing one voice while simultaneously playing another different musical line (voice) is an excellent way to develop our aural (inner hearing) skills. This subject has its own dedicated page: