Transcribing Keyboard Music for Cello

After vocal music, the instrument that has had the greatest amount of wonderful music composed for it must be the piano, along with its keyboard predecessors.

Surprisingly, the transcription for accompanied cello of solo piano repertoire is sometimes a better source of “concert pieces” than the transcription of repertoire composed for other accompanied instruments. This is because the cello’s large pitch range allows us to “raid” from both hands of the piano part, stealing every bit of musical protagonism that we want, making ourselves into the undisturbed and unique soloist (star) of the show, if that is what we want to be. In contrast to this is the situation of transcribing the Violin Sonata literature, in which case the piano normally has a role at least as important (if not more) than the other instrument. For this reason, converting a Piano Sonata into a piece for cello and accompaniment can give us a virtuoso solo piece, whereas transcribing a Violin Sonata for cello will always keep us in the realm of chamber music.

The piano is a self-sufficient musical world, a virtuoso orchestra played with two hands (and a foot), providing simultaneously melody, harmony and rhythm. Allowing a cellist to steal some of their most attractive melodies actually has an advantage for the pianist, especially for those who are missing an arm: it makes their pieces much easier to play as they are now sharing the load with another musician! Let’s hope they don’t mind playing only the accompaniment – and often in a different key to the original version !!

In fact, it is this question of the accompaniments that causes our greatest headaches when transcribing piano pieces for cello because when we steal all of the piano’s melodies and interesting bits, what’s left for the pianist is almost always very thin (sparse, empty). We can’t respectfully ask a “real” pianist to accompany with only one hand (although a learner may not mind) nor can we expect an audience to listen to such an underutilised piano (which would be like having a symphony orchestra on stage but only a few instruments playing). So, in these cases, we have several different possible alternatives to improve the situation for both accompanist and listeners:

- fill out the piano accompaniment with more notes to occupy their free hand/fingers

- fill out the accompaniment in order to adapt it to any available instrumental ensemble

- have the skeletal accompaniment played on guitar or harp: what were too few notes for the piano accompaniment will usually be quite sufficient to occupy a guitarist or a harpist

- remove even more notes from the skeletal accompaniment so that it can be played by a second cello

Once we have solved the problem of the accompaniments, we cellists can enjoy the delights of playing the tunes of Chopin Waltzes, Nocturnes and other assorted musical treasures – and we no longer need a virtuoso pianist to accompany us, as is the case in so much Romantic music for cello (Chopin and Mendelssohn Cello Sonatas, for example). Even some Classical Period piano pieces can be raided for the cello: Mozart’s Piano Sonatas offer some surprisingly wonderful opportunities for theft, especially some of the beautiful slow movements. Many of the faster movements can also be converted into very enjoyable cello duos although the frequent Alberti bass lines that sound so great on keyboard instruments are often much less well adapted to being played on the cello, especially the faster ones. Fortunately, we can often simplify those awkward Alberti-bass string crossings:

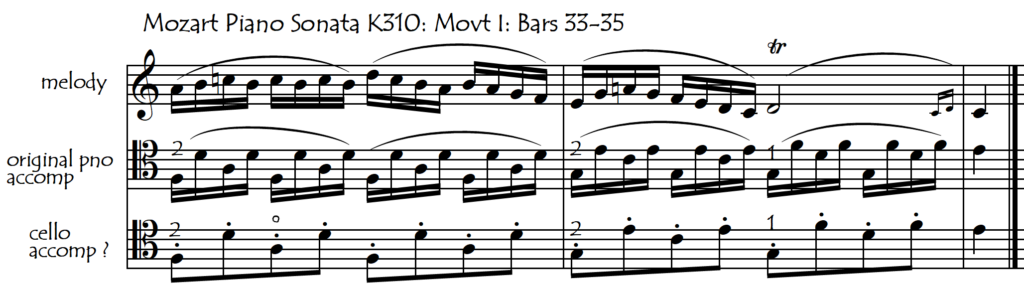

Here is another example of this problem and its possible solution:

RANGE PROBLEMS

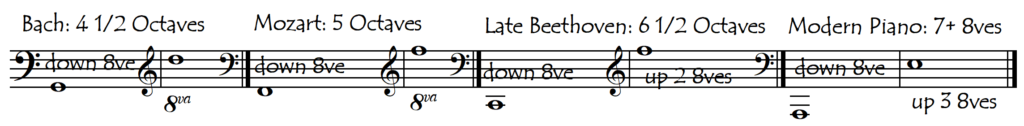

Mozart’s piano music has a maximum range range of about 5 octaves which expanded to 6 1/2 octaves during Beethoven’s lifetime and has expanded since to more than 7 octaves. Even Bach’s keyboard music covers a range of about 4 1/2 octaves.

Because the range of the piano is so much wider than the cello’s, we will often need to modify the original compositions by doing some octave transpositions, raising up the lowest notes (because they are out-of-range for the cello) and, more commonly, bringing down the highest (because they are too difficult up in the cello’s stratosphere). Unlike for the cello, when the piano is taken up into its highest registers for a little musical variety, there is no additional difficulty for the pianist. The literal transcription for cello of a sudden repetition of a passage one or two octaves higher on the piano, for example, may blast us into the dangerous outer-space (highest) fingerboard region and the corresponding dangers may outweigh the benefits of musical interest and authenticity (respect of the original piano score).

ARTICULATION COMPLICATIONS

Because keyboard instruments don’t have to manage a bow, we will often be confronted with keyboard articulations that are difficult to reproduce on a string instrument. In the following example, every second slur takes us out to the upper half of the bow which creates great problems for our spiccato. To solve this problem we will need to either break the slurs, eliminate the spiccato or do some quite virtuosic spiccato bow magic:

*****************************************************

Here is a list of cellofun transcriptions for accompanied cello, of music originally written for solo piano. Occasionally – most notably in some of the Mozart Piano Sonatas – the accompaniment parts that are offered with these transcriptions are quite skeletal. In these cases, rather than filling out the piano parts with more notes, they have been left with only notes that the original composer included. In this way, we can add or remove notes according to the needs of any accompaniment we wish (guitar, harp or instrumental ensemble) or we can get a pianist to complete the accompaniment part according to their pianistic competence: