Doublestops and Chords On The Cello

This article talks about doublestops and chords on the cello. It is however concerned uniquely with the left-hand. For bowing factors in chords and doublestops see String Crossings (bow-level control) in the Bow Technique section.

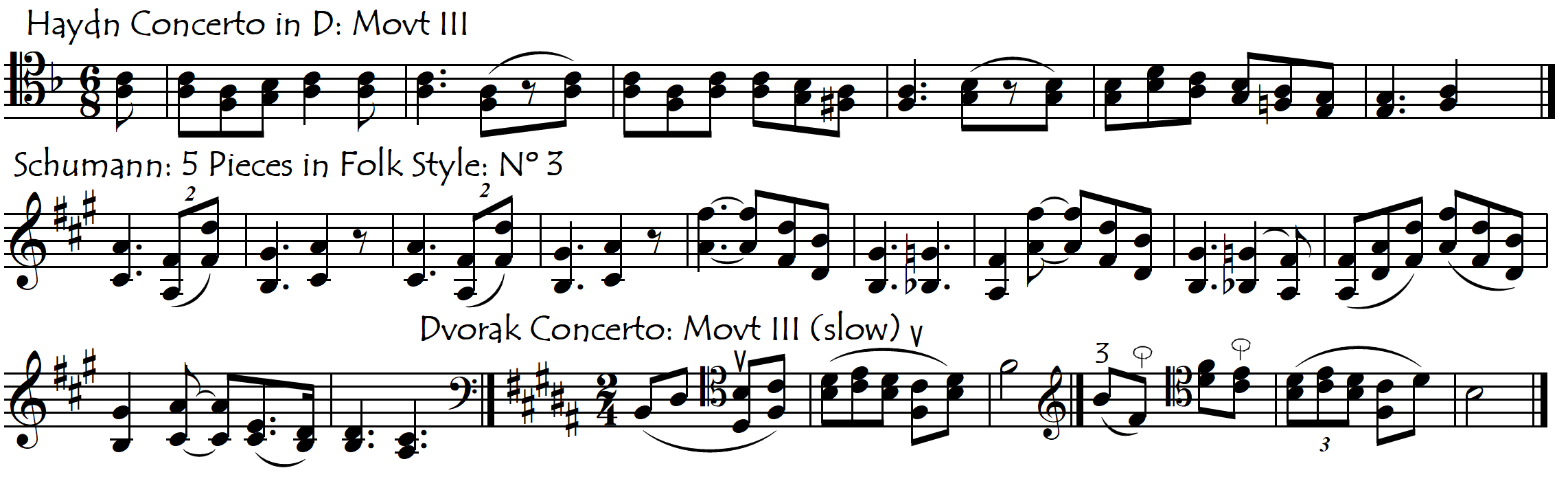

REPERTOIRE COMPILATIONS

For those of us who prefer to avoid (or postpone) reading the detailed analytical discussion about doublestops and chords that follows and would rather go instead directly to some musical material, here below are compilations of passages involving sequences (series) of doublestops and/or chords taken from the cello repertoire (including transcriptions). These compilations have been organised according to their historical period which, as with so many elements of cello technique, also corresponds normally to the pedagogical order: the more modern the repertoire, the more difficult and complex the doublestops/chords tend to be, both for the ear and the hand. One notable exception to this “rule” occurs with the need for thumbposition in the neck region in many Baroque period doublestops, which is quite frequent in all music transcribed from the violin repertoire (and also occasionally in the Bach Cello Suites). In spite of this complication, it may still be a good idea to start with the Baroque compilation and work up towards the Post-Romantic excerpts.

EXERCISES

As we progress down through this article, many different exercises for working on our doublestops will be offered in their respective categories.

DISCUSSION

1: ONE CHORD = TWO (OR THREE) DOUBLESTOPS

We are treating chords and doublestops together here because both require the highly developed skill of simultaneously operating different fingers on different strings. This specific branch of left-hand technique is discussed at its most basic level in the article “Left-Hand String Crossings” in which we talk about our left hand’s “horizontal” positional sense” (knowing where our fingers are across the different strings). Playing chords and doublestops represents possibly the ultimate level of achievement for this skill.

We can consider doublestops as a preparatory step for chords. Whereas doublestops involve only two strings at a time, chords involve three or four strings so, before looking at chords, we will start with a discussion of doublestops. But before jumping into “doublestops” however, we need to take a moment to decide just what is (and isn’t) a doublestop.

2: IS IT A DOUBLESTOP? THE CONCEPT OF “BROKEN” DOUBLESTOPS.

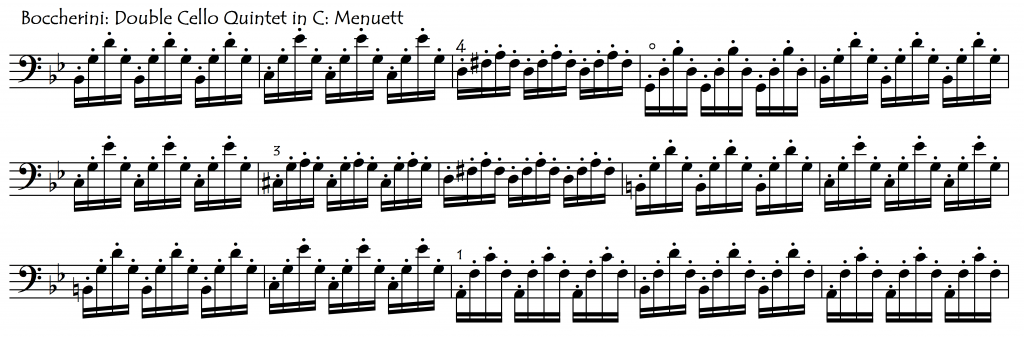

The definition of a “doublestop” is not quite as simple as it may seem, because a doublestop for the left hand is not always a doublestop for the bow (and vice versa). Sometimes something that sounds like a doublestop (sounding two notes at once) is not one, while a passage in which only one note sounds at a time might be constantly in doublestops. This is because the word “doublestop” refers to the left hand’s actions and not to the sounds that we are making. Smoke coming out of your ears? Yes, probably! So let’s use some musical examples, which will make this concept immediately simple and clear:

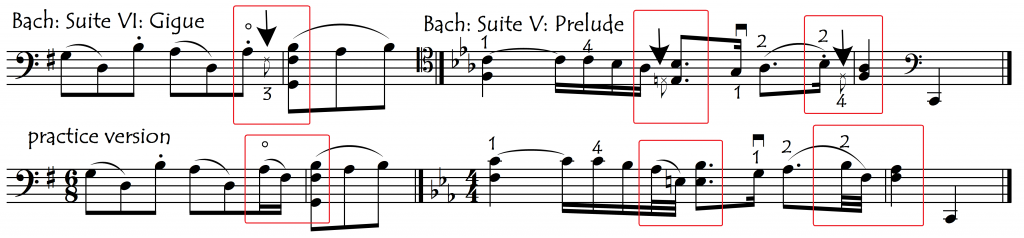

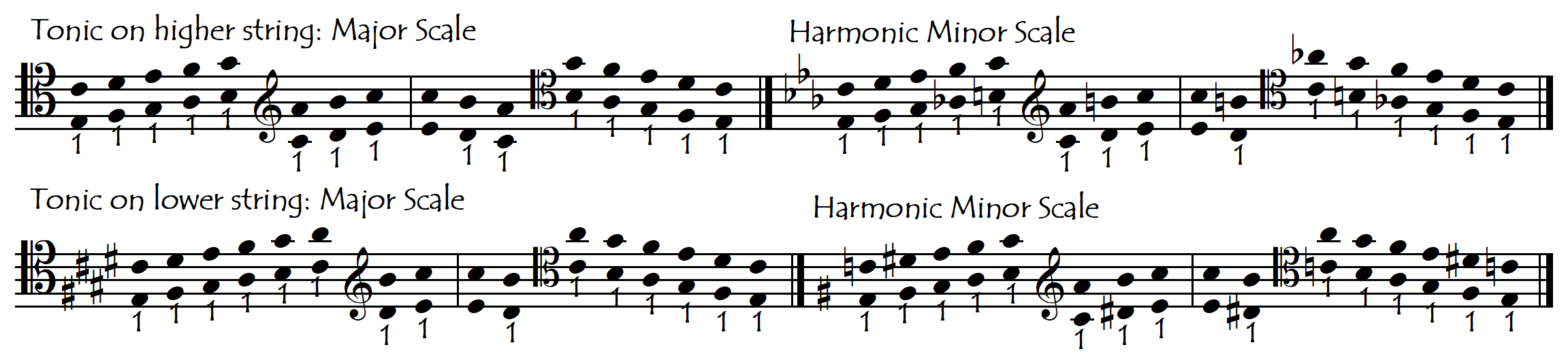

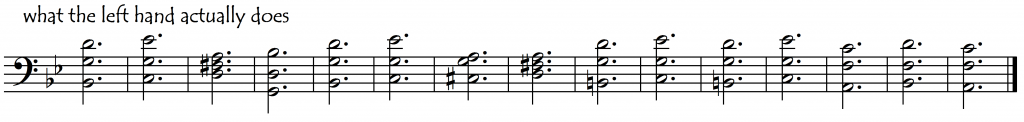

In the first line of examples there are no “written out” (or “sounding”) doublestops: in other words, the bow is only ever playing on one string at a time. In spite of this, however, our left hand is in fact playing doublestops all the time, because it is working simultaneously (stopping) on two adjacent strings. We will call this situation “Broken Doublestops”. The second line of examples illustrates the opposite situation. Here, although the bow is playing on two strings simultaneously, the left hand is in fact only ever playing on one string at a time, because one of the strings in the “bow doublestop” is always an open string (which obviously doesn’t require the left hand to stop it). Below, we have written out what our left hand is actually doing in each of the above examples:

To summarise: just because our bow might be playing on two strings simultaneously doesn’t mean that we are playing “doublestops”. And likewise, just because our bow might only be playing on one string at a time doesn’t mean that our lefthand might not be playing doublestops. No matter what the bow is doing, if our lefthand is working on two strings at the same time, then we are playing “doublestops”!!

Using broken doublestops to practice a doublestopped passage is often a very useful idea. Likewise, practicing broken doublestopped passages as “real” doublestops is also often a very good idea. These subjects are looked into in more detail below, in the section dedicated to “Practicing Doublestops”.

2.1: SHIFTING TO A (BROKEN) DOUBLESTOP: PLANNING AHEAD

Surprisingly often, it may be convenient to shift to a double-stop with our left hand even though there are no doublestops in the music (yes, this is the definition of a broken doublestop). In this way, we use the shift as an opportunity to get our left hand “in position” on both strings, in order to prepare it for a rapid string crossing that comes after the shift. This technique is especially useful when that rapid string crossing also involves an extension. This is best illustrated with some examples. The notes with the “x” noteheads are preparatory notes for the lefthand only: we finger them but do not sound them with the bow.

The decision as to whether we shift to a doublestop or not will depend on how much time we have before playing the finger on the new string:

2.2: BROKEN DOUBLESTOPS: DO WE MAINTAIN THE FINGER PRESSURE PERMANENTLY ON BOTH STRINGS?

When playing “real” doublestops we have no choice: we must maintain the finger pressure permanently on both strings. However, in broken doublestops – fortunately – we can choose what we want to do with the finger which is not sounding. We have three possibilities:

- maintain the pressure

- relax the pressure but maintain the string contact

- release the finger entirely from the string and then rearticulate it when needed again

The following example illustrates these different possibilities:

Maintaining constantly the finger pressure of the non-sounding finger(s) in a broken doublestop adds an enormous amount of unnecessary tension to the hand and is normally not a recommendable thing to do. Whether we remove the non-sounding finger from the string entirely or just relax it (while it’s maintaining string contact) is a choice we can make depending on the circumstances. But without a doubt, relaxing the fingers when they are not in use is an absolutely fundamental technical principle that will help keep our hand flexible, alive and responsive even in the fastest repetitive passages. In fact, the need to maintain constant finger contact is one of the factors that makes passages in “real” doublestops normally so much more difficult than passages in broken doublestops.

3: PLAYING “REAL” DOUBLESTOPS

There is a wonderful saying: “doublestops often make one good player sound like two bad players”. How true this is, certainly for doublestops on the cello !!!

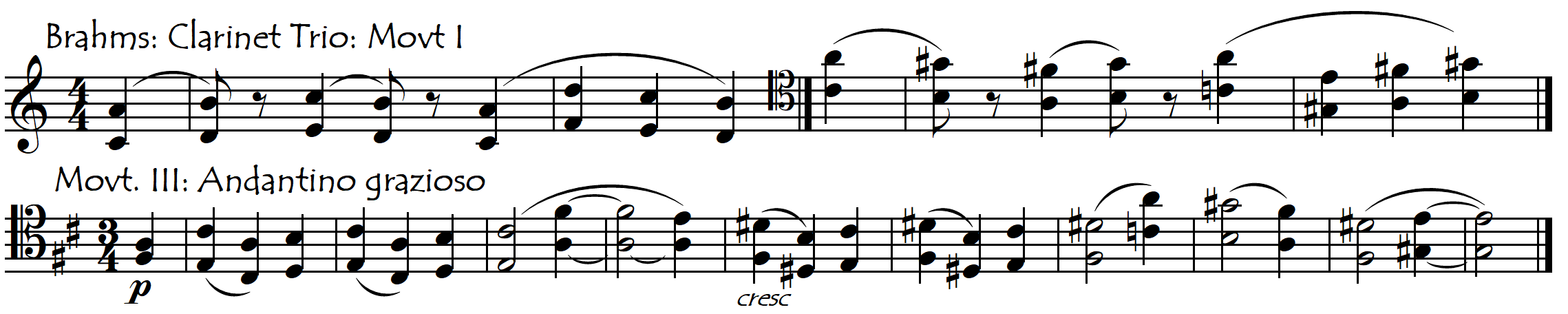

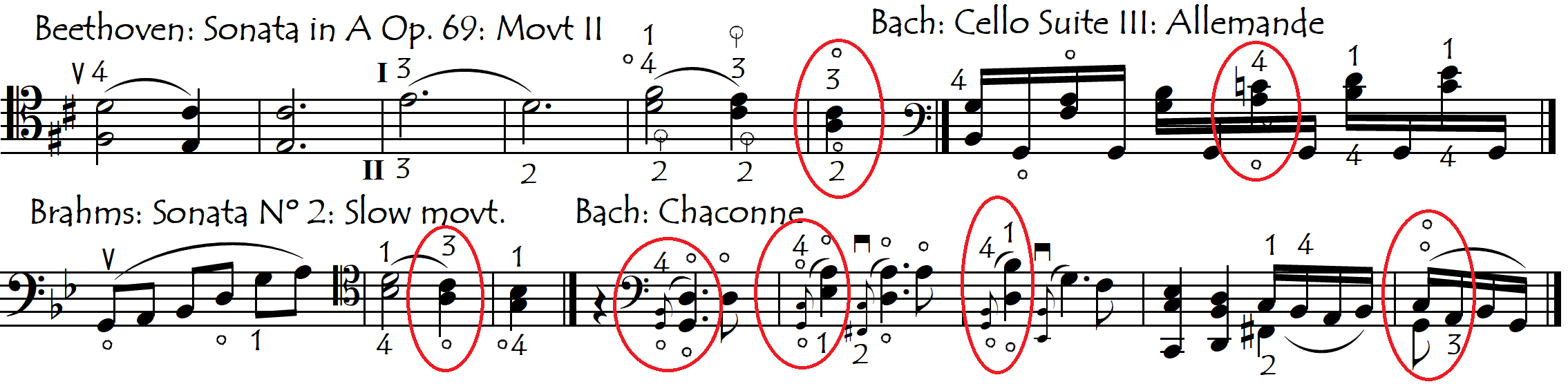

Often, even the very best composers are unaware of the technical difficulties they are creating when they write a passage in doublestops for the cello. If there was a mathematical formula to calculate the level of difficulty, shifting in doublestops would not be the sum of the difficulties of the two simultaneous shifts to the single notes, nor would it be simply twice as difficult as shifting between single notes, but rather it would be the square of all the combined single note shift difficulties! Passages that sound beautiful in the composer’s imagination – and that would sound beautiful if played by two cellists – can be very awkward (and thus easily sound awful) when played in double stops by only one cellist. Here are some examples:

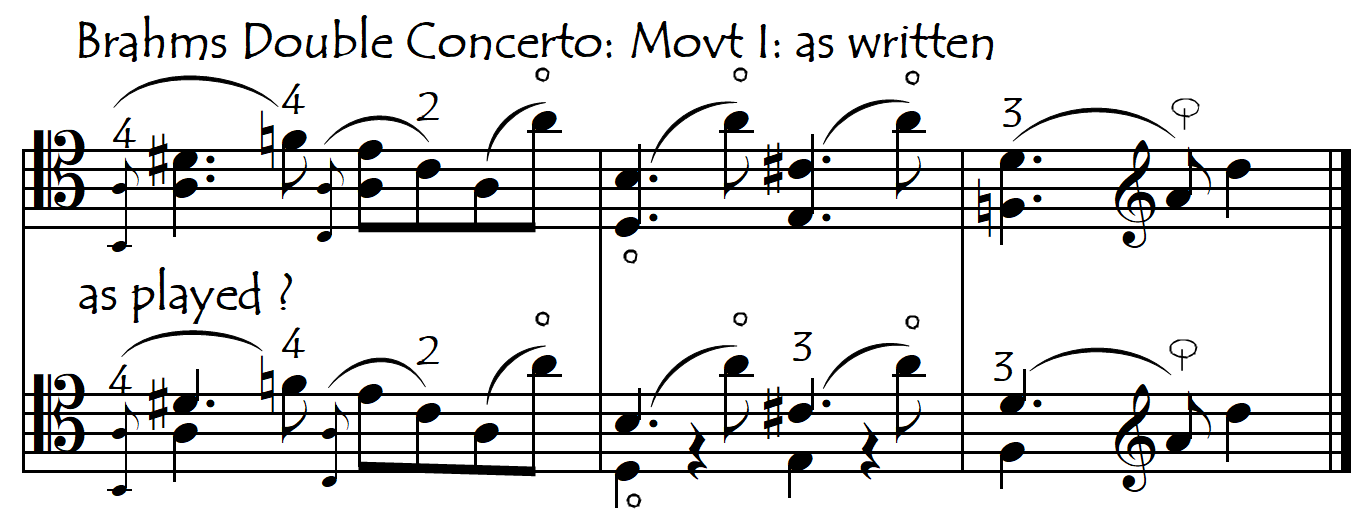

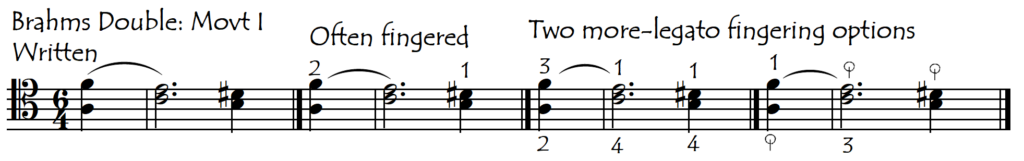

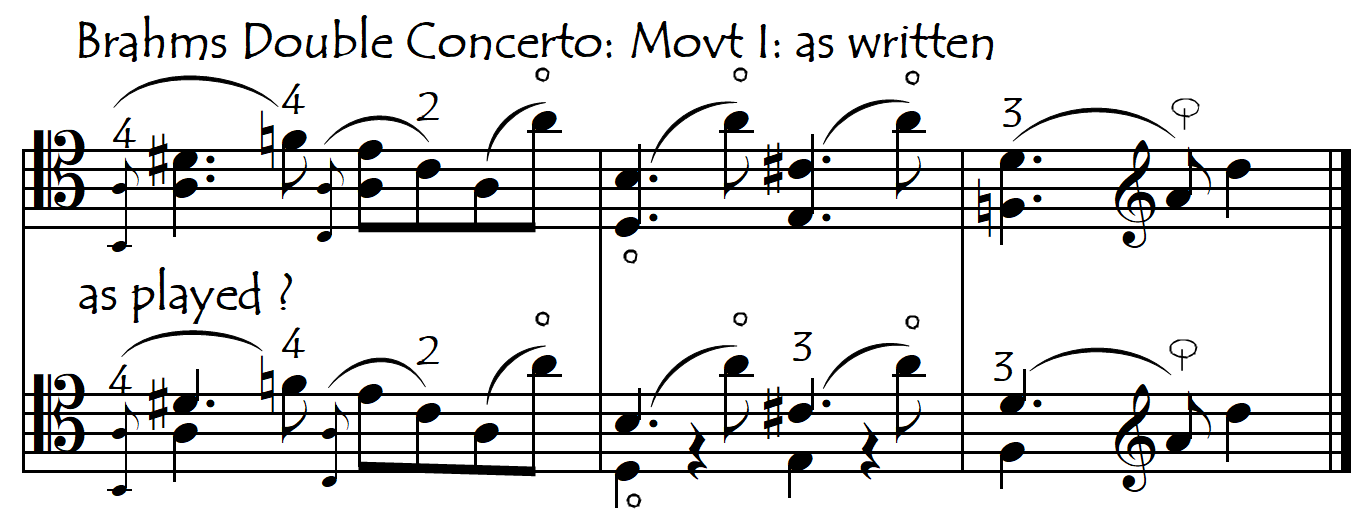

Brahms loved thick musical textures and was particularly “optimistic” with regard to cello double stops. Even in chamber music pieces (with other instruments available to fill in the harmonies or play the contrapuntal line), he gives the cello some rather awkward doublestops, guaranteed to make a lovely melody 10 times more difficult

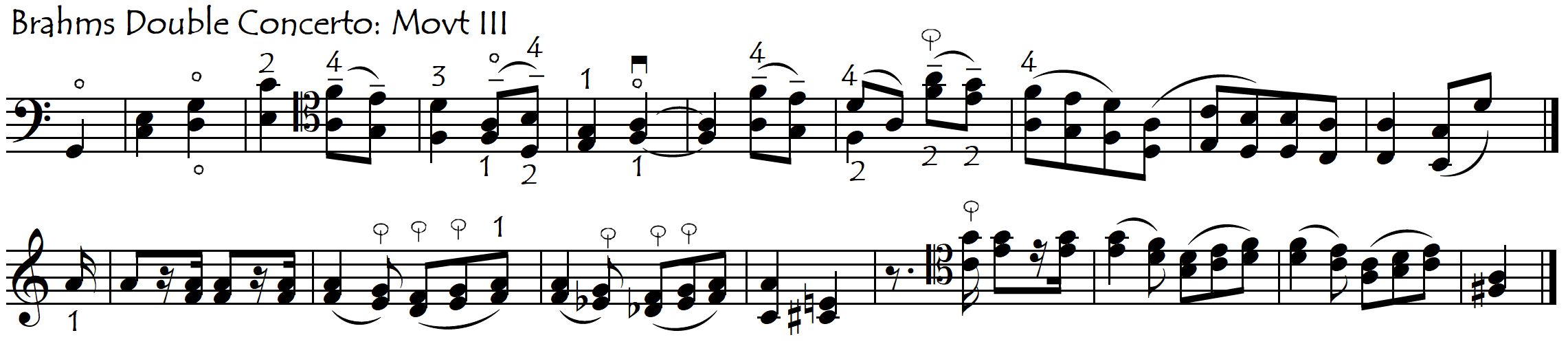

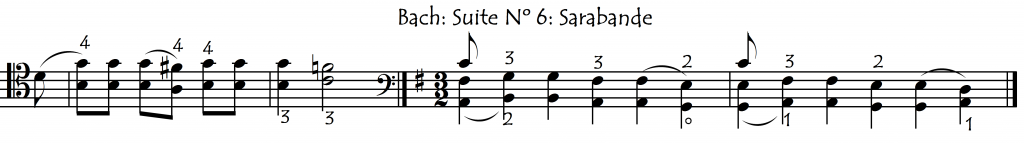

And his “Double Concerto” (for violin and cello) could justifiably be called (and played as) a “Quadruple Concerto” because so much of the solo material is in double-stops!

In particularly difficult orchestral pieces, the solo-french horn players have an assistant who plays certain notes of their part. If each of the two soloists in this Concerto could likewise have an “assistant” to play one of the voices of the doublestops, this piece would probably sound a lot better, and would certainly be a lot more pleasurable to play, especially for a small-handed cellist.

4: DOUBLESTOP REMOVAL (OR MODIFICATION) FOR CELLISTS’ MENTAL HEALTH !

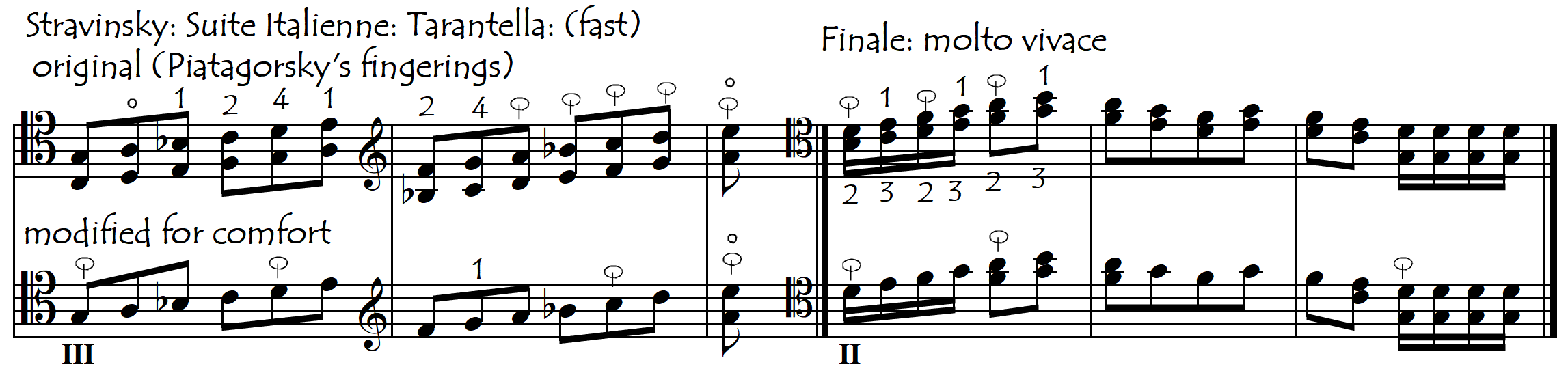

When orchestral accompaniment scores are transcribed/arranged for piano, a very common tendency for arrangers is to try and put as much of the musical material as is possible into the piano part, with the consequence that these piano accompaniments are often very difficult. As we have seen above, the same phenomenon often occurs with composers/arrangers of cello music who, in their desire to create a rich sound, extra melodic/harmonic interest and perhaps added virtuosity/brilliance, are often tempted to add doublestops into their string parts. This situation occurs especially when a composer works with a virtuoso cellist with a huge hand, such as Shostakovich with Rostropovich, or Stravinsky with Piatagorsky, and also in works written/arranged/transcribed by large-handed virtuoso cellists (see the examples below).

A pianist can decide, according to their skill and available practice time, to simplify their orchestral reductions by the removal of many non-essential notes (octaves etc). We cellists could also apply the same principle to our cello parts, asking ourselves the question “is it better to play fewer notes and play them well, or to try unsuccessfully to play as many notes as possible?” !

Because some doublestops can make our lives hugely more difficult – especially for smaller-handed cellists – we may decide that whatever the music gains through their addition is not worth the increase in difficulty, risk, effort, practice time, worry and stress. In other words, we may be tempted to give a little more priority to our emotional well-being and to our audience’s pleasure, and a little less priority to the exact reproduction of the score. In these cases, we have two possibilities, both of which would be of great benefit to listeners and normal-level players but neither of which would be considered acceptable by the more conservative-minded amongst us:

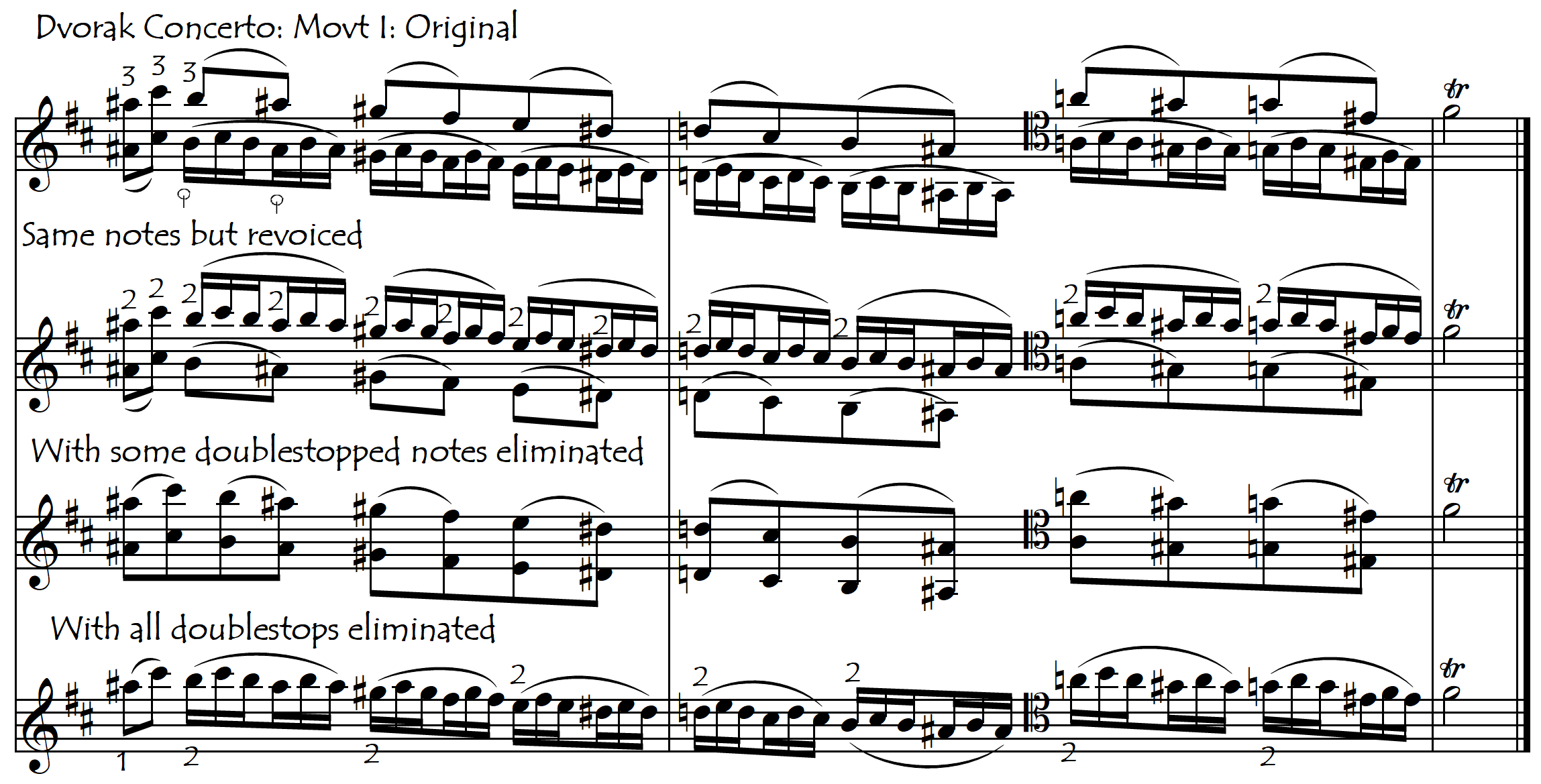

1: we can, as in the following example, revoice the doublestop(s) in order to make them easier:

2: or we can eliminate one voice from some or all of the doublestops:

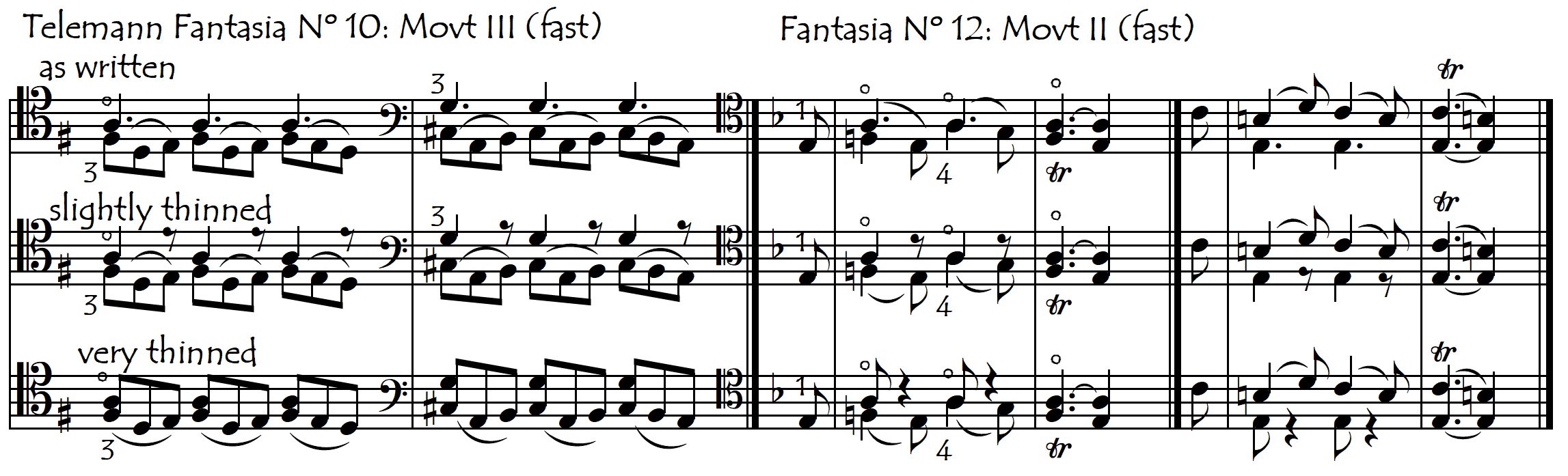

The need for modifications to doublestopped passages arises very frequently when transcribing violin music for cello (as in the above example) because, the violin being so much more suited to doublestops than the cello, its repertoire has a great abundance of them. Unfortunately, many of these are awkward or unplayable on the cello but fortunately, because we are dealing with transcriptions, the elimination or revoicing of doublestops in these pieces will be less controversial.

Even doublestopped passages that don’t require a huge hand can sometimes be thinned out simply to make them hugely easier with very little consequence on their musical effect. Most listeners will not even hear the difference, but every cellist will feel a huge difference !

Perhaps the most simple example of this “thinning-out” process occurs with the suppression (removal) of octaves. This subject is dealt with on its own dedicated page (click on the highlighted link) but we will show one example here for which the simple delaying of the sounding of the higher octave can be a great help in making the shift secure. Now we only have to tune the shift to the thumb, without the higher octave to complicate matters for our ears. Then, once the shift is done, we can add the higher octave. Nobody will hear the difference but the cellist will certainly feel the difference:

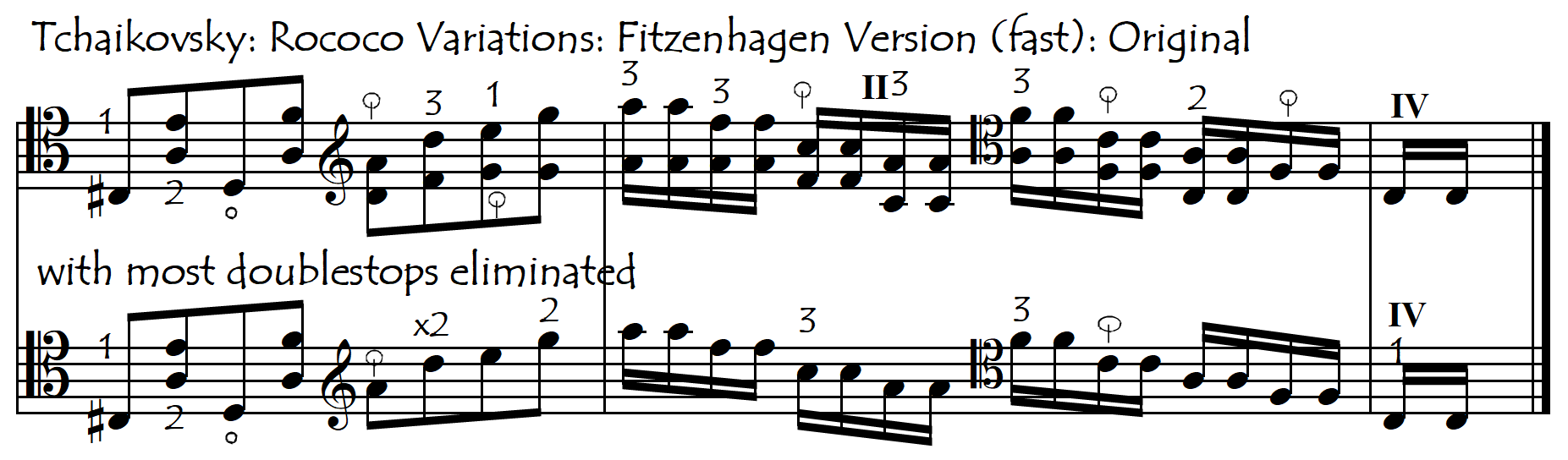

In the following example, three different possible modifications of a notorious doublestopped passage from the Dvorak Concerto are shown, in decreasing order of difficulty:

5: THE FREQUENCY OF DOUBLESTOPS AND CHORDS IN THE REPERTOIRE

Normally, doublestops and chords are most frequent in unaccompanied music, because here we have no other instrument to fill out the harmonies. The Bach Cello Suites and unaccompanied Violin Sonatas and Partitas, as well as the first six Telemann Fantasias, are all full of doublestops and chords The cadenzas of concertos also tend to have a lot of doublestops, for exactly the same reason: in cadenzas, we normally are playing alone, with no accompaniment. They are much rarer in chamber music, and in orchestral music we would be well advised to play all doublestops as divisi. Measurement with a sonometer would probably confirm that a doublestop played divisi does not sound any softer than when both notes are played by everybody in a section, and most composers just don’t understand the high risk associated with playing doublestops in an orchestral setting in which you really can’t hear your doublestop well enough to correct its intonation.

It is a very approximate exercise to try and count the number of doublestops in any piece of music (or passage) because so much of the time the left hand is playing doublestops but the right hand is breaking them. Nevertheless, just for curiosity and in spite of its doubtful utility, we have tried to do this for some of the major cello pieces, in order to compare the frequency of the use of “real” (not broken) doublestops in different repertoire. Here below are the “results”. Drones and other situations in which one note of the doublestop is an open string have not been counted, and if the same doublestop is repeated consecutively then the repetitions are not counted. Chords using two fingers are counted as one double stop, and if they use three or four fingers then they count as two doublestops. Broken doublestops are not counted.

Lalo Concerto 0

Brahms Sonata Nº 1 (E Minor) 10

R. Strauss: Don Quijote 13

Beethoven Triple Concerto 15

Schumann Concerto 33

Brahms Sonata Nº 2 (F Major) 42

Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations 43

Chopin Sonata 55

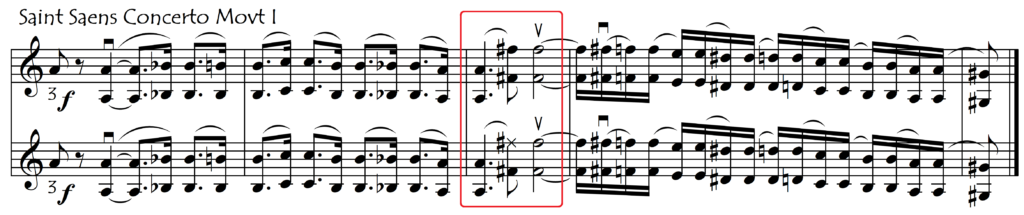

Saint Saens Concerto 70

Elgar Concerto 71

Haydn C Major Concerto 82

Brahms Double Concerto 130

Haydn D Major Concerto 162 (+ Gendron cadenza 78)

Dvorak Concerto 222

Shostakovich Concerto Nº 1 in Eb 390

The following table compares the frequency of doublestops and chords in the different movements of the Bach Cello Suites:

|

NUMBER OF CHORDS AND/OR DOUBLE STOPS IN THE DIFFERENT MOVEMENTS OF THE BACH SOLO SUITES (excluding drones and repeated double stops) |

|||||||||

|

Prelude |

Allemande |

Courante |

Sarabande |

Minuets Bourees Gavottes |

Gigue |

TOTAL |

|||

|

Suite I |

1 |

7 |

2 |

11 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

24 |

|

|

Suite II |

6 |

16 |

5 |

26 |

34 |

0 |

20 |

107 |

|

|

Suite III |

11 |

11 |

1 |

25 |

4 |

1 |

7 |

60 |

|

|

Suite IV |

6 |

3 |

11 |

44 |

1 |

20 |

0 |

85 |

|

|

Suite V |

26 |

31 |

35 |

65 |

0 |

48 |

0 |

0 |

205 |

|

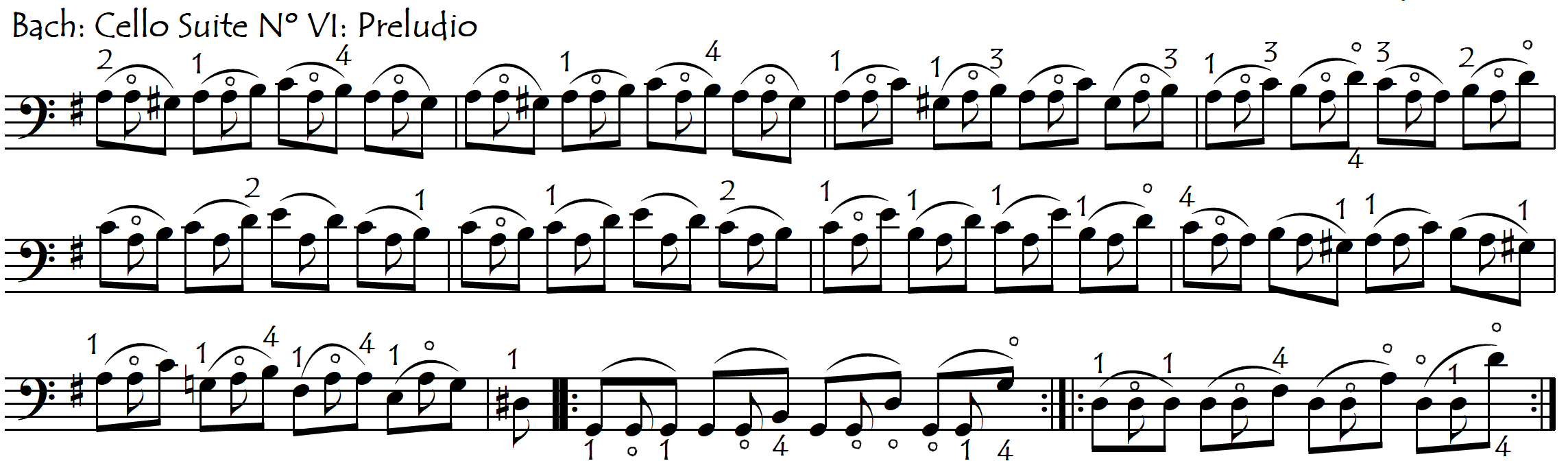

Suite VI |

6 |

24 |

0 |

69 |

42 |

45 |

33 |

229 |

|

A compilation of repertoire excerpts featuring doublestops and chords, grouped according to the stylistic period, can be found at the top of this page.

WHY ARE DOUBLESTOPS DIFFICULT?

There are several reasons why doublestops are soooooo much more difficult than just the sum of the two simple single notes:

1. HAND TENSION:

Significant extra tension is normally needed in the left hand to hold down two notes at the same time, especially when the distance between the two fingers is large. This creates problems not only for our vibrato but also for the fine positioning which is needed to both make a beautiful sound and to play in tune. This problem of added tension is much less severe on the violin than on the cello. On the violin, the distances are smaller. The violinist doesn’t need to stretch/strain their hand very much at all in order to place the different fingers at the same time. This is the reason why “normal” double stops are so much easier on the violin than on the cello, and it is for this reason that many (most) of the original double-stops have been removed from the transcriptions of violin music in their version for cello found on this site. If you have a big hand, or are very flexible, then you can play the cello more like a violin …… and you can put the double-stops back in!

There are some exceptions to this principle of doublestops making the hand tense.

- Doublestops in which the two fingers are close together, create very little added tension and can often sound beautiful, even for a small-handed cellist. Sixths (and fourths) are a good example of this. The further apart the fingers are from each other in a doublestop however, the greater the tension created. Thirds illustrate this perfectly: the major third stretch necessary to play a “simple” minor third interval across two strings is wide enough to create great tension, especially for a small hand. And even the minor-third hand frame can block and rigidify the hand, making vibrato difficult. The discomfort and tension of thirds is made worse by the fact that the higher finger is on the lower string, which is the most unergonomic place for it to be. What a shame it is that passages in doublestopped sevenths don’t sound as nice as passages in thirds!! They are certainly more ergonomic.

2. Most doublestops involving the thumb are exceptions to the “doublestops = tension” rule. This is because the distance between the finger (any finger) and thumb can be opened out widely and easily without creating tension. For this reason, even in the neck and intermediate regions (where we would not normally need to use it) we may prefer to use the thumb instead of a lower finger in some doublestopped passages. The reduction in hand strain that comes from the use of the thumb can significantly help our sound quality as well as facilitate our vibrato. This use of the thumb is especially useful for playing double-stopped minor third intervals across two strings (requiring the major third stretch). Here the use of the thumb eliminates the need for the extended-back first finger on the higher string (which is a real vibrato-killer).

2. AURAL CONTROL: THINKING, HEARING AND TUNING DOUBLESTOPPED PASSAGES.

HEARING/DISTINGUISHING THE SEPARATE VOICES

Keyboard players and guitarists are used to playing several notes at the same time. They thus learn, almost automatically, to hear, think, play and memorise music both harmonically (vertically) and melodically (horizontally. We string players, on the other hand, are principally horizontal, melodic thinkers because we spend such a large majority of our playing time just playing one voice (one note at a time). Because of this, we can be quite weak at thinking and hearing harmonically. When we finally have one of our rare passages in doublestops, our ears can get a little lost amongst the two voices. Trying to distinguish between them and work out what to listen to can appear difficult but is, in fact, largely a question of practice and training.

Surprisingly, even for cellists, used to playing the lower voices, our ears are normally attracted to the higher voice, especially in passages where the two voices move in parallel. We can confirm (or disprove this) by playing different scales in thirds and sixths in which we sing one of the voices and play the other. Usually it is easier to sing the top voice than the bottom voice.

The following link opens up two pages of material (exercises) for working on this aural skill of voice separation:

Exercises For Better Hearing of Doublestopped Sequences

INTONATION

The fact that keyboard players and guitarists don’t need to correct the intonation of each note makes multi-voice playing so much easier for them. But for a string player the situation is very different: playing and correcting two notes at the same time is much more than twice as difficult as playing one note. Hearing and tuning two notes at the same time – even in the same position (without any shifting) – is comparable to doing two different mathematical calculations, not one after the other, but at exactly the same time! When we incorporate shifting into a double-stopped passage, the aural (brain, computing) difficulties increase exponentially, and if we are in thumbposition (with no spatial reference points) and the intervals and fingerings are complex, then those difficulties multiply exponentially once again.

3. FINGER PLACEMENT, INDEPENDENCE AND COORDINATION.

When our left hand is playing on different strings at the same time we not only have the problem of “horizontal geography” (placing several fingers simultaneously on different strings – see Left Hand String Crossings) but also of finger independence and coordination. When playing on only one string, we need to remove all the higher fingers in order to play a lower finger, but when playing on two strings at the same time, this is no longer the case. Suddenly, the possibilities of operating (lifting on and off the string) different fingers at the same time are multiplied exponentially and thus a whole new world of problems of finger coordination, independence and simultaneous finger placement opens up. Further down this page, there is a large section devoted to this skill (see “Cossmann Doubletrill Exercises”).

Jumping a finger from one string to its neighbour in a slurred doublestopped passage is a guaranteed legato-destroyer. Therefore, we might choose to shift more in a doublestop passage in order to avoid the need for the fingers to jump between strings. This “trick” can often allow us to maintain a true legato.

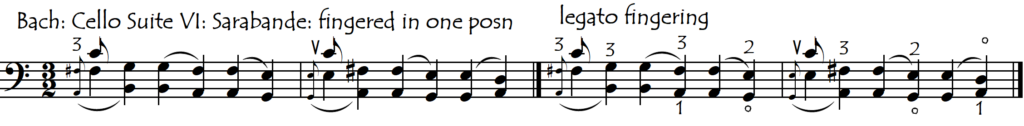

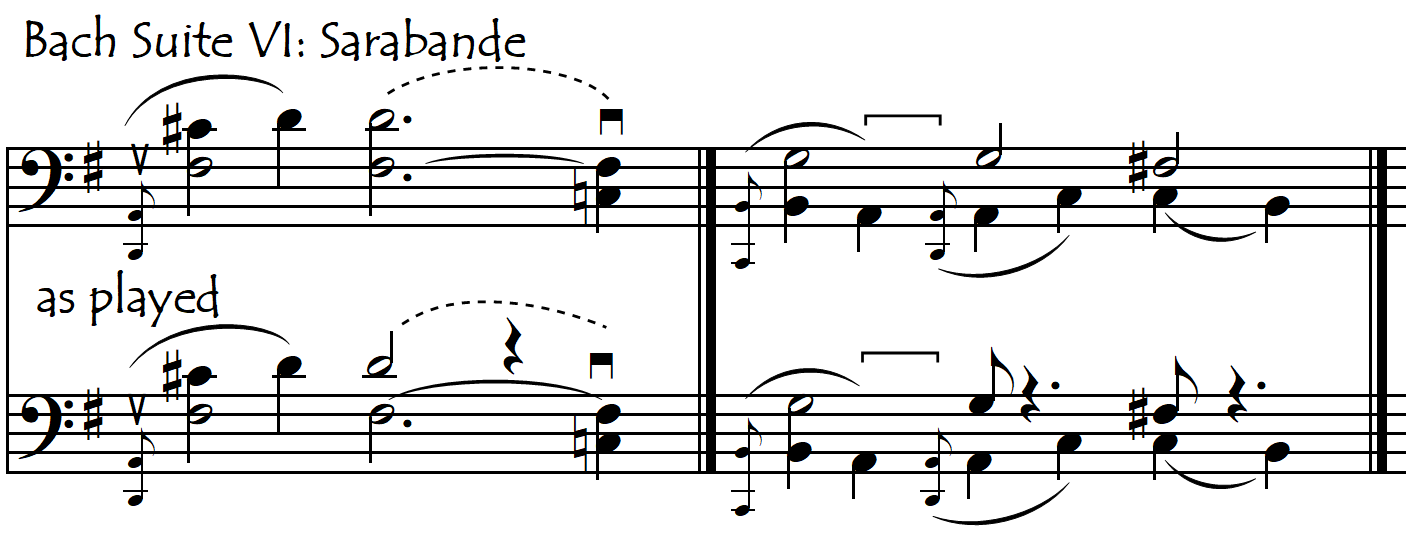

THE DIFFICULTY OF MEMORISING DOUBLESTOPPED PASSAGES

The complexity associated with hearing and playing doublestops means that they – as well as any non-stepwise intervals (broken doublestops) which need to be heard harmonically rather than melodically – are often particularly difficult to memorise. The Bach Cello Suites offer some good examples of this: Gavotte I of Suite V and the Sarabande of Suite VI, with their high frequency of chords and double-stops (see Chords and Double-Stops in the Bach Suites), together with the Prelude of Suite IV with all its leaps (broken doublestops and broken chords) and harmonic writing, are perhaps the most difficult movements in the Bach Suites to memorise. But the cello transcriptions of Bach’s unaccompanied violin sonatas and partitas take this difficulty to a new level: memorising the Fugues, the Chaconne, the Adagio and Sicilienne from the G Minor Sonata, Andante from the A Minor Sonata, Adagio from the C Major Sonata III and the Minuets from the E Major Partita, really puts our harmonic memory skills to the test. The cadenza from the Rococo Variations is another good example of the difficulty of memorising chordal passages.

VIBRATO IN DOUBLE STOPS

Vibrato can “muddy” the intonation of our doublestops so we need to be careful not to try too hard to vibrate wildly on them, even in very romantic expressive music. Perfect fourths and fifths – as in the first chord of the following Elgar example – are very susceptible to “vibrato damage” and benefit greatly from being kept “pure”.

For octaves and doublestopped unisons also, using an intense or large vibrato just seems to create intonation instability and confusion.

This is very strange because if the doublestops were divided among two players, both would be using vibrato and everything would sound great. We might therefore think that it is the synchronicity of the vibrato on the two notes when played by one hand that causes the problem. But if that were true, then violinists would have the same problem with vibrato on doublestops (which they don’t) ! To add to our confusion, on the last chord of the above Elgar example, we can vibrate to our heart’s delight on the F# of the last chord without any “muddying of the waters”, thanks to the fact that the other note of the doublestop is an open string. How sad then, that on a normal doublestop, it is not possible to vibrate only on one of the two notes!

In some ways, the need for less vibrato on doublestops is fortunate. Most double-stops create additional tension for the left hand and we know that forcing vibrato onto a tense hand usually gives the opposite effect to the musical warmth that our vibrato is supposed to create !! One way we can add vibrato without muddying the doublestop, especially for strained hand positions, is to shorten one of the notes (usually the bottom note) and then add vibrato to the note that is being played alone. In other words, we vibrate only at the end of each double-stop (or chord), by which time we are only playing with the bow on one string (usually the higher string). So in fact we only vibrate on one note of the doublestop (usually the top note) which, with the release of the other finger, is now totally relaxed.

In this way, we get the best of both worlds: the note that has been shortened continues resonating on its own and stays in our ear (or in the listener’s imagination) like a sustained doublestop, but we can also add a beautiful melodic vibrato to the passage. Try this, especially in the last two bars of the above example.

This phenomenon of an excessively wide vibrato muddying the harmonies is often heard in its most extreme form with operatic singers. A capella (unaccompanied) vocal quartet passages (such as in the last movement of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony and various moments of Verdi’s Requiem) are often sung with such wide operatic vibratos that the sense of harmony, tonality and tuning is completely lost. Rather than music, the end result sounds more like a wild-animal bellowing competition in the jungle!

DOUBLESTOPS AND REGISTER

The lower the register, the more our doublestops become “muddy” and unclear. Somehow our ears gradually lose their ability to distinguish the pitches as we get into the lower registers and doublestops eventually lose all their harmonic utility. Rather than adding richness they just obscure the harmonies and if we add vibrato to these low-register doublestops the mud just becomes thicker. Perhaps elephants and hippopotami would not have the same problem but for humans, a succession of low doublestops on the C and G strings can sound more like animals grunting or furniture being dragged across the floor rather than music.

This is why in many cellofun transcriptions, low doublestops have often either been eliminated or have been revoiced to bring the lower note up an octave. In the cello duo (and violin + cello) versions of many of Mozart’s Piano Sonatas, for example, it has been found that filling out the harmonies in the lower cello part with doublestops (even easy ones) as were used in the original piano’s left-hand is actually counter-productive, certainly in the lower registers. It is much more successful to keep the bass-line simple and monophonic, letting our ears imagine the missing harmonies.

ORCHESTRAL (AND ENSEMBLE) DOUBLESTOPS: AN ERROR OF ORCHESTRATION

Because of all the difficulties associated with doublestops, in orchestral playing, no matter what the composer specifies with respect to the doublestops that they write, the end result will almost always be better if we play them “divisi” (divided up) with our stand partner. The common wisdom of “united we stand, divided we fall” could not be more wrong when applied to double stops. When we divide them up (by playing them “divisi”) the section will sound good, but when we play them “united” we can easily bomb!! Even in chamber music, it may be possible to redistribute the notes among the different players to improve or eliminate awkward doublestops: certainly, pianists usually have a spare finger available to lighten our load and this can make the difference between pleasure and suffering ….. for both player and listener.

A good example of the use of divisi for orchestral doublestops can be found at the beginning of the final movement of Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony. In a totally transparent texture, where every tiny bit of out-of-tune playing can be heard immediately, Beethoven writes a series of low sustained doublestopped fifths (F and C) for the cellos. Fifths are the hardest doublestop to play in-tune and the lower register is the hardest one in which to hear and tune our doublestops. This is absolutely nothing to be gained for a cello section by trying to play these as doublestops. In fact, this passage is almost an IQ test for a section principal (or conductor). Anybody who suggests that “because Beethoven didn’t write divisi we must play them as doublestops” should change jobs. Even better, they should take two new jobs and try and do them at the same time !

THE GOOD SIDE OF DOUBLE STOPS

They may be difficult to play and very ungrateful in performance, but double-stops are a wonderful tool for practicing. They develop, in an accelerated, concentrated and highly efficient way, many extremely useful skills, such as:

- strength in the left hand (practicing double-stops is like doing weightlifting)

- awareness of the different finger positions within any one hand position (because now we can hear the finger spacings simultaneously rather than consecutively)

- awareness of the different hand positions on the fingerboard (positional sense)

- intonation (ear training and aural control)

- finger independence and coordination

- horizontal (across the strings) positional sense

- bow level control.

If we can play (and shift on) two notes quite well at the same time, then when we only have one note to play (or shift on), it will feel fantastically easy. Imagine a dancer who practices with weights attached to their arms and legs and a blindfold over one eye: when the weights and the blindfold are removed, everything feels easy. It’s the same for us cellists: doublestops are an excellent training tool for both hands and for our ears/brain. For example, compare the following two shifting exercises, one in doublestops and the other with single notes. The exercise in doublestops is incomparably more efficient and useful.

Even if there are not many doublestops (or none at all) in a piece we are playing, much of that same music is often made up of “broken doublestops”, for which practicing in “real doublestops” is the best preparation. Consider the following example:

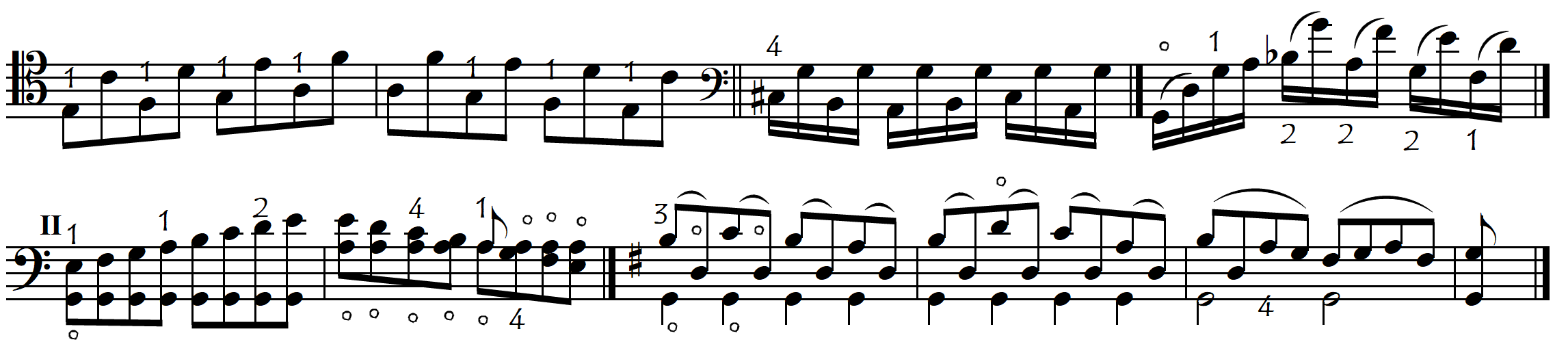

DOUBLESTOPS IN ONE POSITION (NO SHIFTING)

When we work (practice) with doublestops, we are not just learning “how to do doublestops” but are actually using doublestops as a turbo-powered practice tool through which we can establish and develop our fundamental left-hand cello technique in the most intense, concentrated, and efficient way. Our technical work with doublestops can be structured in a progressive manner. At the most basic level, we can start with material that doesn’t involve shifts. Doublestopped exercises in any one position (with no shifts) are magnificent for building strength, finger independence, finger coordination and for establishing perfect finger spacings. These multiple skills are not only necessary for playing doublestops, but are also extremely helpful for our normal (non-doublestopped) playing.

Some of the best exercises are “doubletrill” patterns in which different possible finger combinations and alternations on any two adjacent strings are used. The cellist Bernhard Cossmann was the first to “discover” and publish some of these exercises in his “Studies for Developing Agility, Strength of Fingers, and Purity of Intonation for Cello” in the late 19th century. One of these many possible finger permutations is shown here below. Although this example uses “close” (non-extended) position, these exercises can also be done in the extended position.

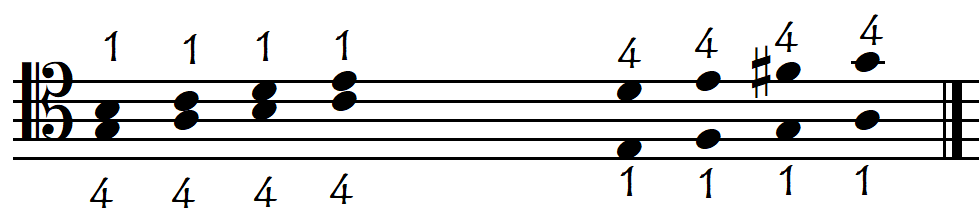

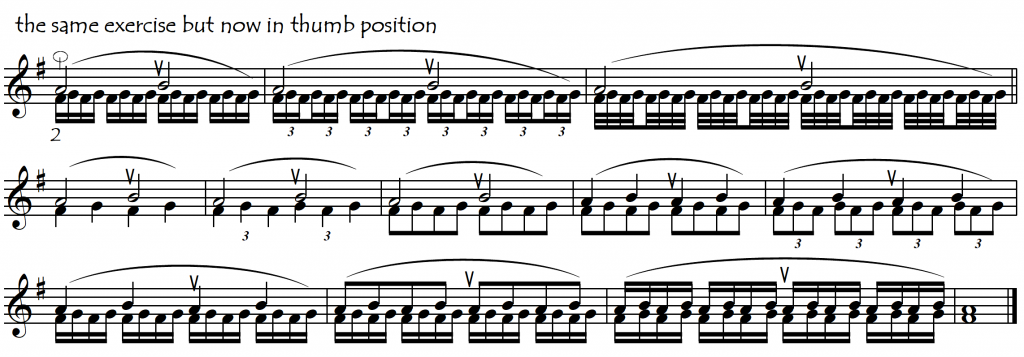

On the cellofun.eu website, these exercises are developed, elaborated, and extended, forming the basis for our left-hand technical foundations. These exercises are very physically intensive, muscular and strenuous, and we should work on them very gradually. In order not to overstrain the hand, all of these exercises start without any major-third handframe extensions. These are only added gradually at the end of each series. We can use these and other similar exercises not only in the Neck Region but also in the Intermediate Region and in Thumbposition (see Fingerboard Regions), as each of these has not only a completely different hand posture but also different fingering possibilities. Here below is an example of how these exercises are perfectly transposable into the thumbposition.

In thumbposition, we can do these exercises also using the flattened second finger (F natural in the above example) as well as with both the first and second fingers flattened (Bb and F natural in the above example).

In the Intermediate Region we only really have three fingers (instead of the four that we have in the Neck and Thumb positions), so we cannot do the “doubletrill” exercises (which require two fingers on each string). Nevertheless, we can still use doublestopped exercises involving all the different possible two-string finger configurations as the basis for our left-hand technique in this region.

Here then are our complete compilations of the many different doublestop possibilities in any one position, for all three of the cello’s fingerboard regions. In these exercises we have preferred to be complete rather than concise: some of the finger permutations are extremely awkward (if not totally impossible) and some are horribly dissonant. Others however are both very harmonious and easy to play.

- Doublestopped Exercises in One Position: NECK REGION

- Doublestopped Exercises in One Position: INTERMEDIATE REGION

- Doublestopped Exercises in One Position: IN THUMBPOSITION

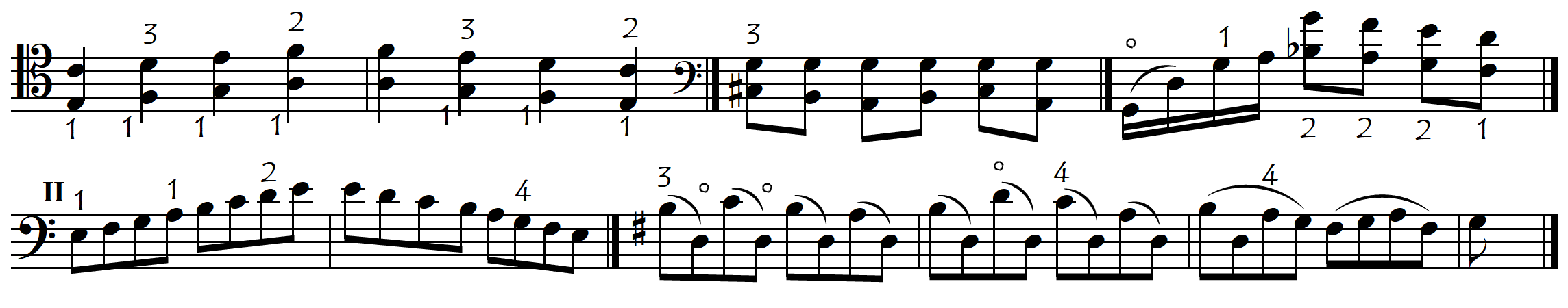

THE NEED FOR SHIFTING IN PASSAGES “IN ONE POSITION”: FROGS AND LEGATO FIFTHS:

Frogs move by jumping but in doublestopped legato (slurred) passages we may need to shift (rather than jump) in order to avoid the break in the legato line that is unavoidable when we “jump” a finger across to the lower neighbouring string. Even sliding the same finger over to the fifth above on the higher string can break the legato line. Both of the following examples could be fingered in one position, without any shifts, but they will sound more legato if we do some small shifts, effectively using finger substitutions to play the broken fifths:

SHIFTING DOUBLESTOPS

This large, complex and fascinating subject has its own dedicated page here:

HOW TO PRACTICE DOUBLESTOPS

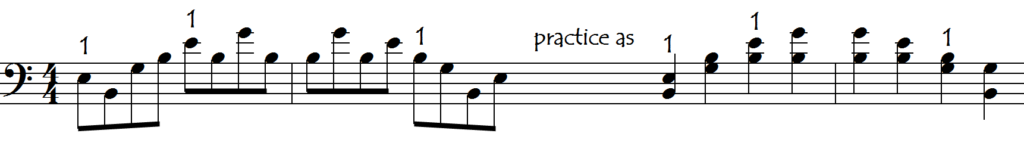

Doublestops can and should be practiced in the same way that pianists practice their two hands: separately. But while pianists practice each hand individually, we will practice each string individually. We can use three different graded preparatory levels of separation to work up progressively to the finished doublestop passage.

- at the first and easiest level we practice each string separately, using the same fingering as we would when paying the doublestops but without bothering to finger the notes on the “other” string. Here, not only is our ear/brain freed from the difficulty of controlling both musical lines simultaneously but also our hand is freed from the physical complication of playing on two strings simultaneously.

- the next level of difficulty is to play (bow) each string separately while also simultaneously (but silently) fingering the notes on the other string. In this way, our left hand is doing everything it will ever have to do in the passage, but our ear/brain is still free to focus on one line at a time.

- next, we can play them as broken doublestops, starting on both the top and bottom string successively, as in the following illustration which uses a simple scale in thirds. Broken doublestops are undoubtedly the best, most painless, way to learn and work on doublestopped passages. With broken doublestops, there are also almost unlimited possibilities to create exercises for Bow Level Control (string crossings) on two strings.

- the final step is to play both strings together.

SEPARATION OF THE TIMING OF THE FINGER ARTICULATIONS IN DOUBLE STOPS

Sometimes in doublestops, we will place both fingers simultaneously. This is especially common when we have plenty of time to do so comfortably:

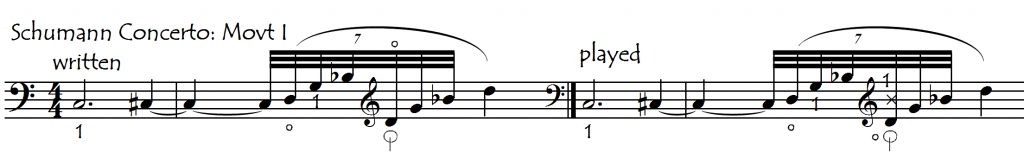

At other times however, it may be helpful to place the two fingers at different times. Normally this means that we will place the finger on the “new” (silent) string slightly before we actually need to sound it with the bow. By doing this we don’t need to coordinate its articulation (placement) with the bow’s arrival on the new string: the finger is already there. It also means that we don’t need to coordinate the simultaneous articulation of both fingers of the double-stop, once again because one of the fingers is already prepared. This means that even though we are playing a double-stop with the bow, for the left hand we are converting the beginning of the double-stop into a broken double-stop. This can make double-stops much easier, as in the following examples. In the “practice” version of this example, we deliberately sound this anticipated finger placement with the bow. This is a good way to practice this little trick as it makes the anticipatory placement of the finger audible and thus much more deliberate.

More discussion about this can be found in the article on Anticipation.

BREAKING THE ENDS OF DOUBLE STOPS (NOT MAINTAINING BOTH NOTES FOR THEIR FULL VALUE)

We have seen that we can convert any doublestop passage into “broken” doublestops as both an aid to learning the required left-hand skills and also to make exercises for bow-level control (string crossings) on two strings. But even in a performance situation, we very often break doublestops that are written out as non-broken. In other words, we will often cut short one of the notes of a doublestop (i.e. stop bowing on that string) in which, according to the score, each note should have the same rhythmic value. This “break” is however usually imperceptible as it is at the end of the stop, and it is almost impossible to notice that one note of the pair lasts less than the other, because the note that we have stopped bowing continues sounding both in our imagination and in the room’s resonance. There are several reasons why we might want to do this.

- MUSICAL IMPOSSIBILITY

Many Classical and Baroque composers systematically write the doublestop for as long as it is harmonically valid, even if playing it for its full written duration is technically or musically impossible. In the following illustration from the C major Fugue of Bach’s Unaccompanied Violin Sonata Nº 3 for example, the only way to maintain the long note for its full length would be to slur the upper notes. This is “musically impossible” as it would change the character of the fugue theme completely. Obviously, Bach never meant for the long bottom notes to be actually played by the bow for their full written value. Both Bach and Telemann do this always, and we can usefully apply the lessons of this example to most of the doublestopped passages of the Baroque and Classical eras.

This shortening of one of the notes of the doublestop is not only important musically but is also technically useful. It allows us to reduce left-hand tension and is often a big help in our preparation for the next note, both for the bow and for the left-hand. The shortening doesn’t necessarily have to be always on the lower note of the pair.

Here is another example, this time from the cello repertoire. The top stave shows Haydn’s notation. The second stave shows how that would actually sound if we were to play it literally:

To avoid repeating the lower notes of the three doublestops which require a change of bow on the higher string, we can play the following adaptation:

- TO MOVE ONE OF THE DOUBLESTOPPED FINGERS TO ANOTHER STRING

This can be in the same hand position (no shift):

Or in preparation for a shift to a new string:

- TO REDUCE HAND TENSION AND ALLOW A RELAXED VIBRATO

Strained hand positions, as occur in many doublestops, greatly interfere with our vibrato. Forcing vibrato onto a tense hand usually gives the opposite effect to the musical warmth that our vibrato is supposed to create and we need to find a way to overcome this problem. If we release one finger/note of a doublestop early (stop playing it) then our remaining stopped finger is immediately freed from this additional tension and can now vibrate freely. The note we have stopped playing continues resonating on its own (or in the listener’s imagination) and, at the end of the doublestop, we are in fact only playing one note of the doublestop (usually the top note) which, with the release of the other finger, is now totally relaxed.

- SIMPLY TO LIGHTEN THE TEXTURE

We can choose to release one of the doublestopped notes as a way to lighten the texture, making the music more transparent. We can sometimes choose just how much we want to do this; shortening to a greater or lesser degree one of our doublestops:

“UPSIDE-DOWN” DOUBLESTOPS

Very often we can make use of doublestop fingerings in which the higher open string is used as the lower note of the double stop as in the following examples:

There are several reasons why we might want to use these fingerings instead of the “normal” fingerings:

- the use of the open string gives greater resonance to the note and gives absolute intonation security

- it may remove the need for an extension, thus reducing hand tension

- we may be able to avoid a shift

Upside-down doublestop fingerings can be quite confusing for our brain (ears) and hands because we are so accustomed to having the lower notes always on the lower strings. Try the following extreme example, in which the note on the lower string is one octave higher than the note on the higher string. With the harmonic on the lower string and the open string on the higher string, we have no problems with our intonation, and the doublestops are extremely resonant. This fingering is perhaps the best cello substitute for the same notes one octave higher on the violin, which lie in first position with the open A string on the bottom of the doublestop.

In all of the above examples, our use of “upside-down” doublestop fingerings is a choice, but often, we have no choice and are quite simply obliged to move our left-hand up and down a lower string while using the higher string as a “pedal” or “drone”. Here below is a link to a page of repertoire excerpts in which we can or must use these types of “upsidedown” fingerings:

Upside-Down Doublestops: REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

Bach was an expert in creating special effects using fingerings of this type, often using them with quite complex string-crossing bowings.

These types of passages are looked at also on the “Upsidedown String Crossing” page.

CHORDS

Chords can be considered as a slightly more complicated version of doublestops. The same ambiguity with respect to their definition applies to both chords and doublestops. Just because the bow may be playing a 3 or 4-string chord doesn’t mean that the left hand is also necessarily playing on the same number of strings:

Likewise, the opposite situation – that of “broken chords” – is often true. Here, even though the bow might be playing only single notes (one string at a time), the string crossings occur so quickly that the left hand must maintain fingers stopped on more than two strings at the same time. It is as if we were playing chords on the guitar. Broken chords are exactly like broken doublestops, just with the fingers on more strings at the same time:

Even though we can never really play with the bow on more than two strings at once, this situation in which the left-hand is playing on three or four strings simultaneously is quite common. And of course in pizzicato chords we can – unlike with the bow – actually play on three or four strings at once, either with a four-finger-pluck or with a guitar strum.

The following link opens a library of as many of the possible four-string chords that I could find on the cello. Only the most fundamental, simple harmonic chords have been included. This means only major, minor and dominant seventh chords, in all their possible inversions, together with diminished sevenths. Undoubtedly, some have been missed, which is why gaps have been left for the additions.

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL

Chords and Double-Stops in the Bach Suites

The wonderful cellist Johannes Möser has a very fine 15-minute video here about cello doublestops which is well worth watching.