The First Finger

ARTICULATION-ON-DEMAND OR LADY-IN-WAITING? THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HOW WE SOUND OUR HIGHER AND LOWER FINGERS

The higher the finger (using standard notation of thumb,1, 2, 3 and 4) the more it is played by active finger articulation as compared to being played by the release of a higher finger. The thumb almost never needs to be articulated (hammered onto the string) in order to be played: once it is placed on the string it just stays there permanently, ready to be used when we need it. The first finger is only actively articulated after the open strings and after notes played by the thumb: after any of the other (higher) fingers it is just there, waiting on the string just like the thumb (if we are using thumbposition). The second finger has to be articulated after the open string, thumb and first finger notes: but after notes played with the third or fourth fingers it is just there waiting on the fingerboard. In order to sound (play) the top finger however, it almost always has to be actively articulated. The only finger after which it doesn’t need to be articulated is itself!

In summary: the lower the finger, the more it tends to function as a “lady-in-waiting” and the higher the finger the more it tends to function with “articulation-on-demand”

ON THE GREATER IMPORTANCE OF THE LOWER FINGERS

The lower the finger is (using standard finger notation of 1, 2, 3 and 4), the more important it is as a “foundation” for the hand. There can be nothing dainty and hesitant with these “lady-in-waiting” lower fingers – in fact, the lower fingers need the strength and power of the palace guard. There are several reasons for this:

- the lower the finger, the closer it is to the thumb and to the central axis of the hand and arm. The ring shape formed by the thumb and first finger is not only our main positional reference for the left hand and arm but also constitutes the main structural support for the whole hand. This frame needs to be particularly strong and stable.

- it is the lower fingers that are most in contact with the fingerboard. When we are using a higher finger, the lower ones are still usually touching the fingerboard whereas when we are using a lower finger, the higher ones have to be moved away from the fingerboard. So the lower the finger, the more time it spends in contact with the fingerboard.

- the lower the finger, the more often it is used for Scale/Arpeggio shifts and as Intermediate notes in Assisted shifts.

ON THE GREATEST IMPORTANCE OF THE FIRST FINGER

The first (index) finger is very appropriately named. It is the cellist’s strongest and most important finger. It is our hand’s home base, foundation, pillar of strength and captain of the finger team. Of all the fingers, it is the one that we use the most, and is the finger with the strongest positional sense. Even when we are not actually stopping the string with it, it is the finger that spends the most time in contact with the strings because the only time we need to actively and deliberately remove it is when we are stopping the string with the thumb (or playing on the open-string). It is our most frequent finger of choice for intermediate notes, both in shifting and in finding new hand positions “out of the blue” (finger placements without glissando).

The strength of the first finger is vital for almost every aspect of our left-hand technique, but most especially for two specific areas: extensions and shifting. It is the first finger that supports the strain of the vast majority of the extensions that our left-hand does, and it is the favoured finger for shifting on, especially in upwards shifts because of its extreme stability in that direction (see Fingering).

Ascending scale shifts on one string provide a very good example of the absolutely fundamental importance of our same-finger shifting skills on the first finger, for which finger strength is the most important prerequisite. Even though the finger choreography goes from a higher finger to a lower finger, the shifts are basically just same-finger shifts on the lower finger (most commonly the first finger). Therefore a prerequisite for good fluent secure scales on one string is the optimal functioning of these arpeggio-interval same-finger shifts on the first finger.

Also, in our Assisted Shifts it is the lower finger (usually the first finger) that is most commonly shifted on even though we can (and often do) shift on the higher finger:

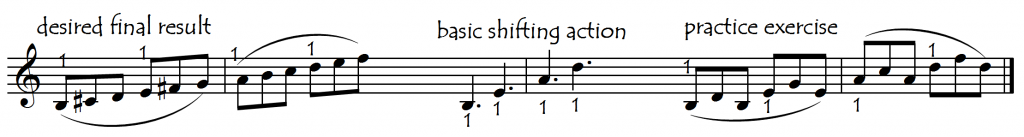

Practice material in which we always shift on the first finger is excellent for building its strength. Continue transposing the following exercise upwards through the different fingerboard regions and play it on the different strings:

Click on the following links for some very efficient practice material to develop first-finger shifting strength and security. These are intensive “workout” exercises for building first-finger strength using shifts on the first finger in all the fingerboard regions:

First Finger Stepwise and Scalic Shifts First Finger Shifts Thirds

First Finger Shifts Fourths: No Extns First Finger Shifts Fourths: Always Extended

Larger Shifts on The First Finger

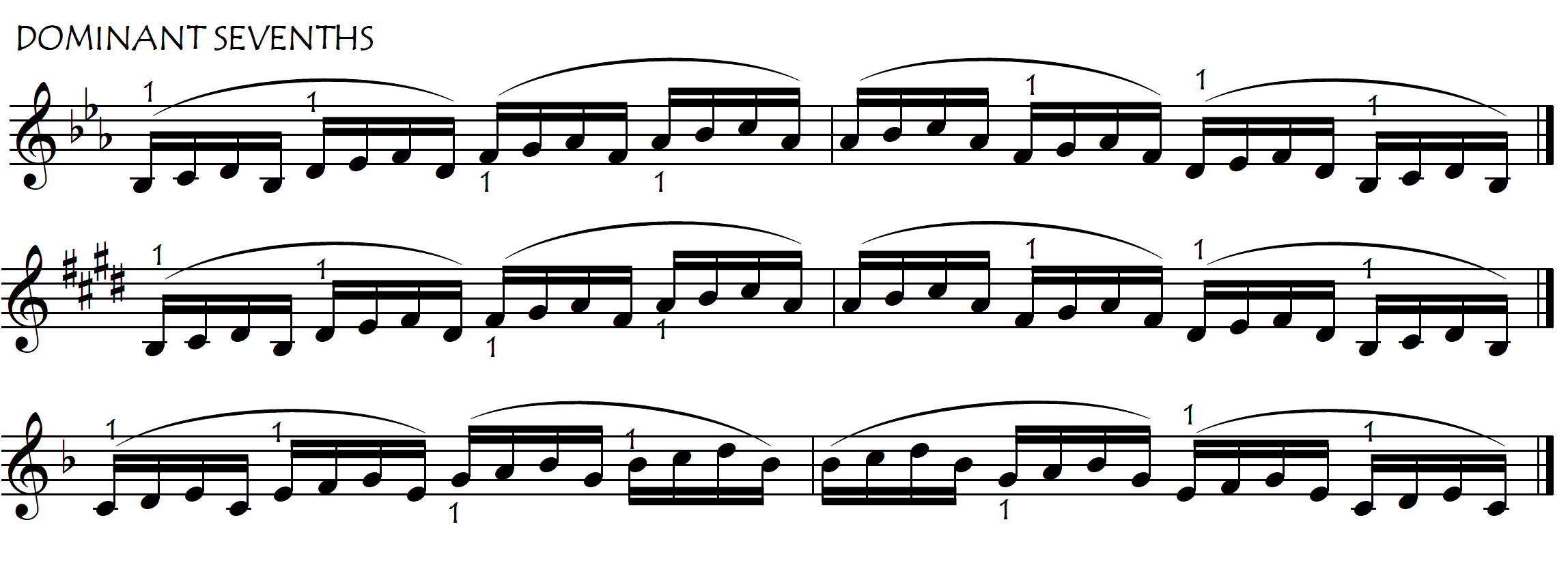

We can also develop the shifting strength of our fingers by practising exercises that shift “to” the finger, not just “on” it. But in order for this to be effective, we will need to do the slide on the new finger (rather than articulating it on arrival). Upwards scales (see above example) and arpeggios not only need great base-finger strength, they also are good at developing it, for example:

Or, another example:

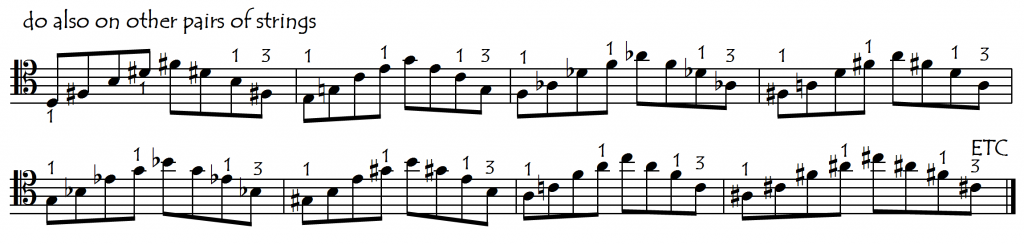

Here now are some more exercises, this time based on shifts to the first finger from other fingers:

Major Third Arpeggio Shifts Between Second and First Fingers: No Extensions

Minor Third Arpeggio Shifts Between Second and First Fingers: Always Extended

Scale/Arpeggio-Type Shifts To Extended First Finger

DISCOMFORT OF THE FIRST FINGER IN THUMBPOSITION

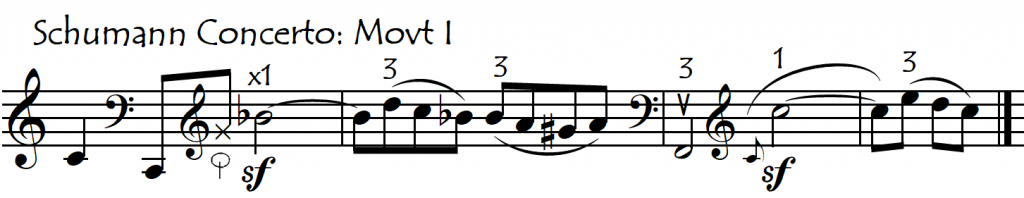

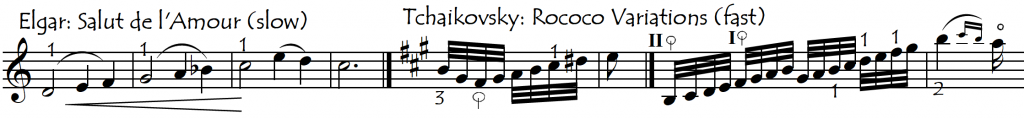

The first finger in the Neck and Intermediate fingerboard regions is the hand’s powerhouse, foundation and pillar of strength. But when we place the thumb up on the fingerboard (Thumbposition) that same first finger suddenly loses most of its superior qualities, becoming weak and insecure. This is because it is just too close to the thumb for optimum stability/ergonomy. The problem is especially pronounced on the A-string because the obligatory hand position – especially for cellists with a short thumb – means that the first finger doesn’t have room to have its nice ergonomic curve and must play often with the last finger joint blocked in a rigid, straight line. Strong climactic notes played on the first finger in Thumbposition on the A-string can be quite unsatisfying because of this unergonomic finger posture:

And big shifts up to supposedly powerful notes on the first finger can be dangerously unstable.

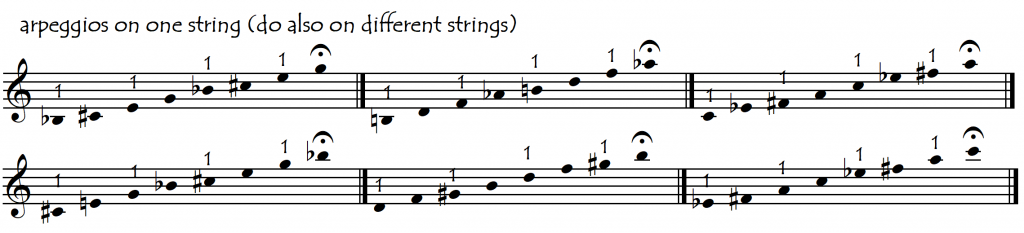

Usually, it is this first-finger weakness and instability that causes the main problems with upward scales on the same string in Thumbposition:

For all these reasons we need to work especially on our first finger strength in Thumbposition. The Cossmann Doubletrill exercises, together with the shifting exercises given below, are very good for this. Apart from this “hard physical work”, some other easier solutions (using our intelligence) are also available. Placing the thumb only on the A-string can help facilitate the comfort of the first finger, thus minimising this problem somewhat. Removing the thumb entirely from the fingerboard (allowing it to “float”) does even more to help.