Shifting Doublestops

Some of the best exercises that we can do for our left-hand at the cello (see below) involve shifting doublestops.

Doublestopped exercises in any one position help enormously with our strength, coordination and intonation and are an absolutely necessary preliminary stage to the more difficult skill of shifting on (or to) doublestops. Shifts involving doublestops are much more difficult than shifts which involve only single notes, so if we can do any particular shift in a doublestop, then doing that same shift on single notes will feel easy.

With doublestopped shifting, we move into a very complex world in which all the difficulties of doublestops-in-one-position are now magnified and multiplied by the addition of the shifts. This is rocket science for cellists and it will help to move into it gradually, by progressively adding new complexities for both the ears and the fingers. One way to do this is to practice on the two strings in the same way that pianists practice their two hands: separately. We can use three different graded preparatory levels of separation to work up progressively to the finished doublestop passage.

1. At the first and easiest level we practice each string separately, using the same fingering as we would when paying the doublestops but without bothering to finger the notes on the “other” string. Here, not only is our ear/brain freed from the difficulty of controlling both musical lines simultaneously but also our hand is freed from the physical complication of playing on two strings simultaneously.

2. The next level of difficulty is to play (bow) each string separately while also simultaneously (but silently) fingering the notes on the other string. In this way, our left hand is doing everything it will ever have to do in the passage, but our ear/brain is still free to focus on one line at a time.

3. Next, we can play our passage as broken doublestops, starting on both the top and bottom string successively. Broken doublestops are undoubtedly the best, most painless, way to learn and work on doublestopped passages.

The main lefthand factors that determine the difficulty level of a doublestopped shifting passage are:

- shift sizes and speeds (normally faster and/or larger = more difficult)

- finger coordination challenges

- aural complexity of the intervals

- hand frame changes during the shift

Let’s explain this last point, which is especially applicable to shifts in which there is no change of fingers during the shift:

HANDFRAME CHANGES DURING SHIFT

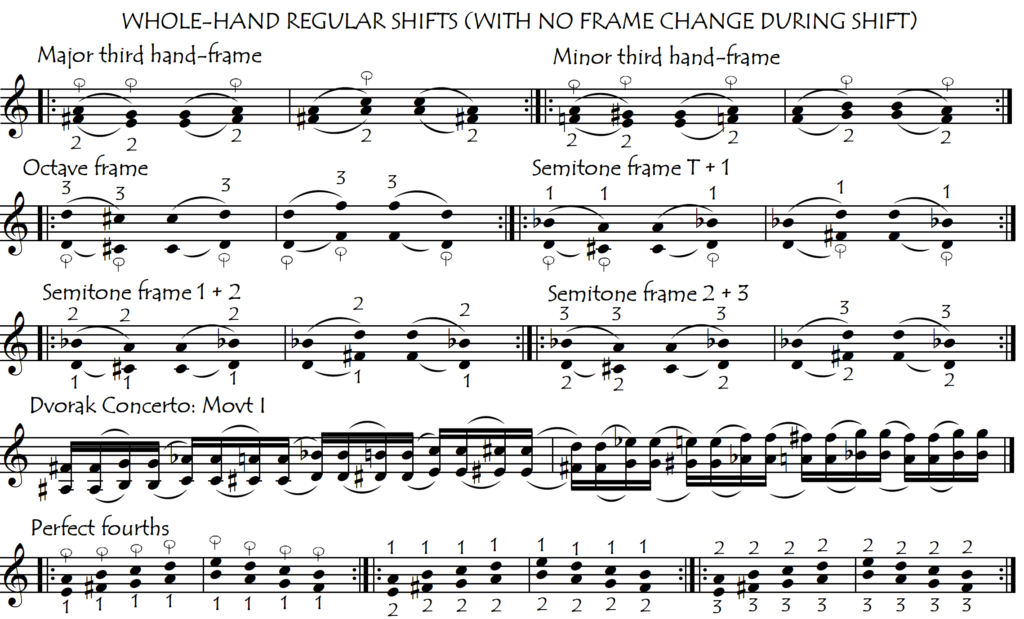

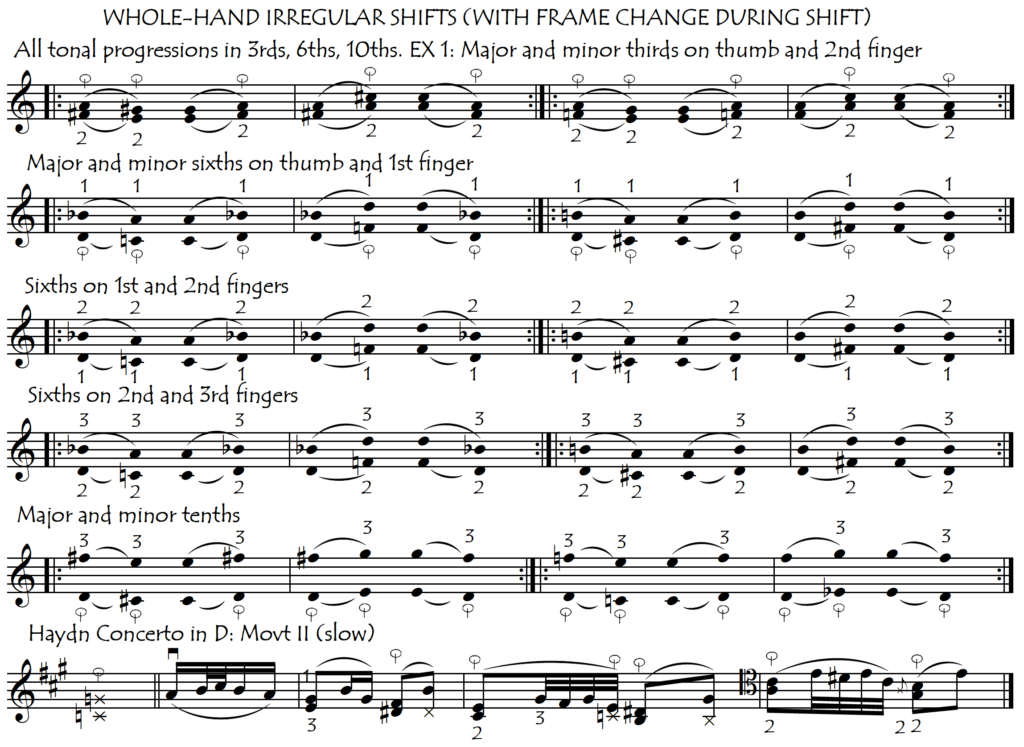

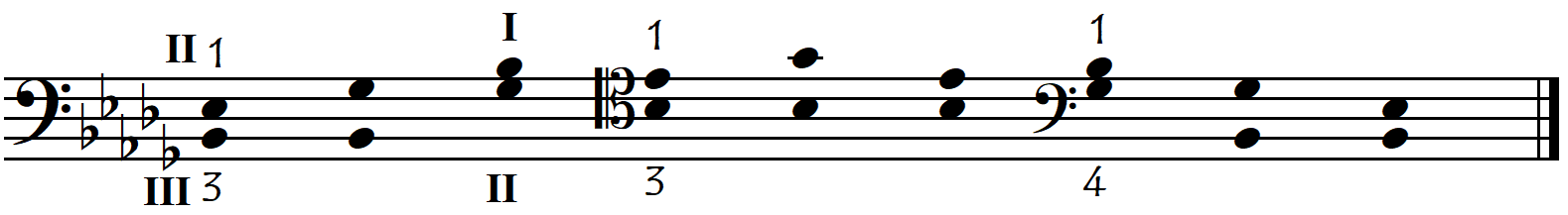

Look at the following examples. They are all in the midrange of the fingerboard and make use of the thumb, but all of them can be equally well transposed down into the Neck Region without the thumb. The first five lines show two-bar cells in which the musical distance (interval) between the fingers does not change during the shifts. We will call these “Whole-Hand-Regular” shifts:

The following examples, in contrast to the previous ones, illustrate shifts in which the hand frame (musical distance between the playing fingers) DOES change during the shift. We will call these “Whole-Hand-Irregular” shifts:

While octaves have no frame change as we shift them around the fingerboard, thirds, sixths and tenths change between minor and major in any tonal sequence (but not in chromatic sequences), meaning that the distances moved between the two notes of the doublestop are not always identical. As a general rule, it is more difficult to control the tuning of those shifts in which the hand frame changes during the shift. In other words, when the two fingers of a same-finger doublestop shift move by different intervals during the shift, this makes it harder for our ear, brain and hand to control the shift. The following link opens a page of exercises and musical excerpts designed to explain and work on this concept of “whole-hand-regular” and “whole-hand-irregular” doublestopped shifts. All of the examples are in thumbposition but most can also be transposed into the neck position:

Whole-Hand-Regular and Whole-Hand-Irregular Doublestopped Shifting: EXAMPLES

RIGHT-HAND FACTORS IN DOUBLESTOPPED SHIFTING

The most useful way to work on our doublestopped shifts is to slur them because this makes the glissandi especially easy to hear. For this reason, almost all of the shifting exercises here are presented as “rolling” shifts in which each doublestop is played twice, firstly as the target (of the shift or string change) and then as the departure point towards the new doublestop. As we become more comfortable with our doublestopped shifting we can progress to the next stage of difficulty, which involves doing the shifts now on separate bows (not slurred). We still however need to make sure we keep our glissando smooth and relaxed.

*********************************************************

So let’s now work out how we can build up a gently progressive series of exercises to work on our doublestopped shifting. Let’s start with the smallest intervals, no finger changes, and no frame changes during the shifts.

DOUBLESTOPPED CHROMATIC SCALES

Doublestopped scales move stepwise and have no coordination problems because they are normally played with the same-finger shifts. The most pleasant intervals to use in doublestopped scales are thirds, sixths, octaves, and perhaps even fourths. Chromatic scales move by the smallest interval (semitones) and have no changes of handframe so let’s start our doublestopped shifting adventure with these.

From a physical (hand, ergonomy) point of view, chromatic scales in thirds, sixths and octaves are the simplest introduction to doublestopped shifting. However, from an aural point of view they are not so simple, which is why we incorporate many open strings in the following exercises in order to check our intonation as we move up and down.

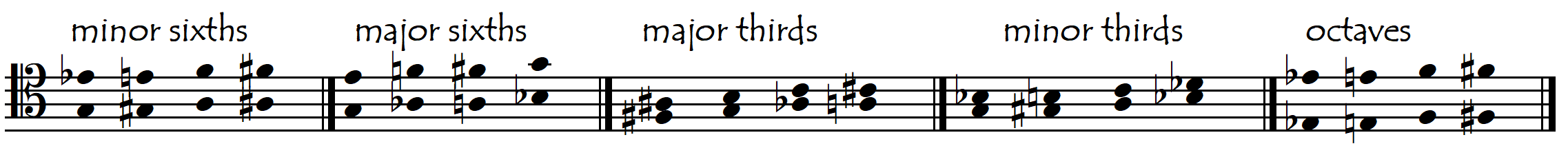

We will start with the closest finger spacing which is one semitone between neighbouring fingers. This gives us either an augmented fourth (if we have our higher finger on the lower string) or a minor sixth (if we have our higher finger on the top string). We will prefer the minor sixth for our first chromatic scale exercise as this is a much more pleasant interval than the augmented fourth. The next wider finger-spacing is the whole tone, which gives us either a perfect fourth or a major sixth, depending on which string we put the higher (or lower) finger. We will use the major sixth because, once again, it is more pleasant than the fourth. We follow the same principles for the minor and major third finger-spacings, finishing with the perfect fourth finger-spacing of doublestopped octaves. This gives us five different chromatic scales, each with a slightly wider finger spacing:

Doublestopped Samefinger Chromatic Scales: EXERCISES

DOUBLESTOPPED MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES

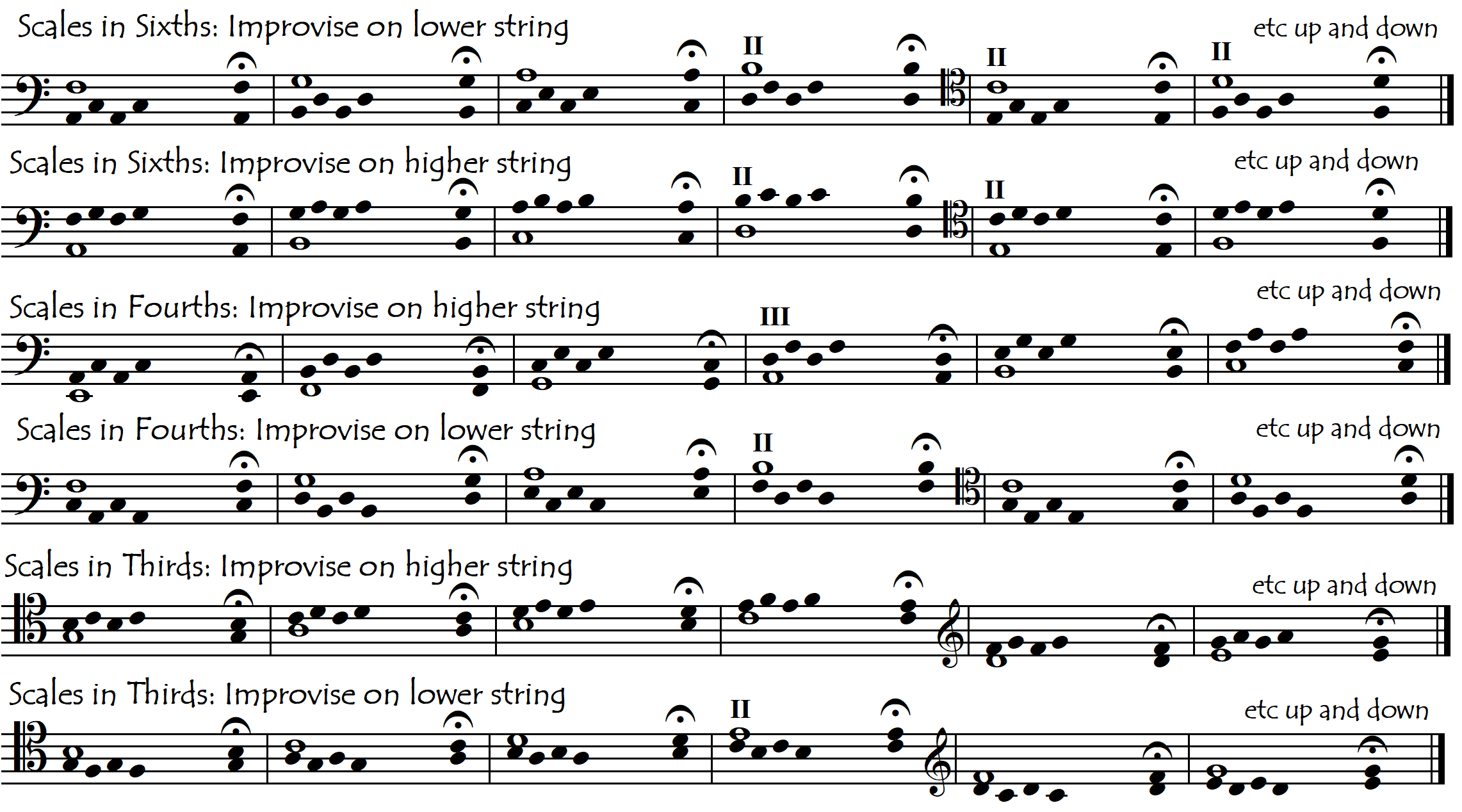

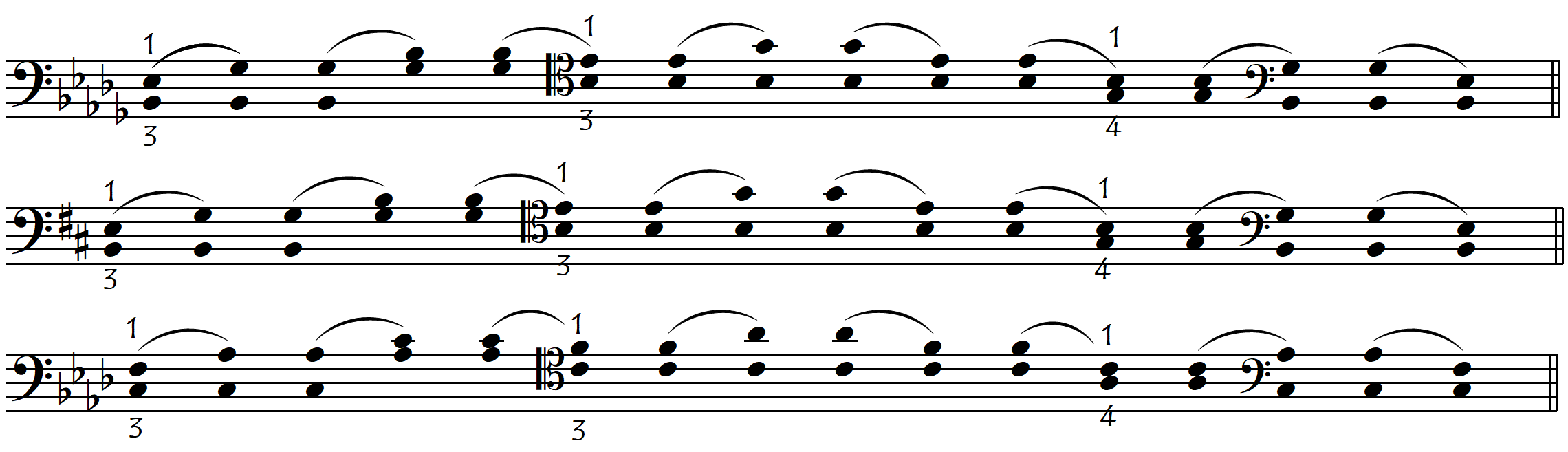

Standard major and minor scales in thirds, sixths, octaves and fourths are an OK next step in our progression of difficulty, but they become even more useful when we add an additional note/finger in each hand position. When we play them in this way these are some of the most efficient and useful exercises that exist for our left-hand at the cello. They develop both our hand strength and our sense of fingerboard geography as well as being the best method for establishing our correct finger spacings in each hand position. No other exercise is as good for helping our intonation. The following examples can be played on different pairs of strings and in different keys. They can also be played in thumbposition: just replace the first finger with the thumb and change the other fingers correspondingly.

These foundation exercises can be downloaded and printed via the following link:

Doublestopped Samefinger Scalic Shifting: PRELIMINARY EXERCISES

Below is a link to a compilation of transposable major and minor one-octave scales featuring doublestopped samefinger shifts. The doublestopped intervals used are thirds, sixths and octaves. All of the different stepwise, same-finger shift fingering possibilities are used, including also the use of the thumb in all of the fingerboard regions. Each scale is played successively with the tonic on both the higher and lower string. There are no changes of string within each scale (in other words, each scale stays on one pair of strings) but each scale can be played on any of the three pairs of strings (A/D, D/G, and G/C). The scales are written out in the “rolling” version in which each doublestop is played twice: once slurred to the previous doublestop and once slurred to the following doublestop. In this way, our shifts are always slurred, which makes it very easy to hear our glissandi and thus control the shift intonation. The next stage in difficulty would be to play the scales with only one bow per doublestop, hence with the shifts falling always on the bowchange.

With its seven pages and 84 scales it looks quite intimidating, but the idea of this compilation was simple curiosity and the desire to explore every possibility. There is no need to play all of them. This material can be considered as “food for thought” rather than “efficient pedagogy”.

Doublestopped Major and Minor Scales

DOUBLESTOPPED ARPEGGIOS

The above examples all use stepwise, samefinger shifts. Doublestopped shifting exercises using arpeggio intervals are the next progression in difficulty level, not only because the shifts are now larger but also because we are now changing fingers during the shifts on at least one of the strings. Even though the arpeggio exercises may be somewhat more difficult, they are a delight to play because the harmonies are so pleasant, and the effect of the constant doublestops is to make the cello really ring like an organ. These are excellent left-hand warmup exercises as they take us all over the cello register.

Once we start to look for the different possible doublestopped arpeggio progressions (sequences) we soon realise that there are a very large number of these, so they have been divided up into different groups:

- without extensions and with no use of the thumb

- with extensions but with no use of the thumb

- with thumb position

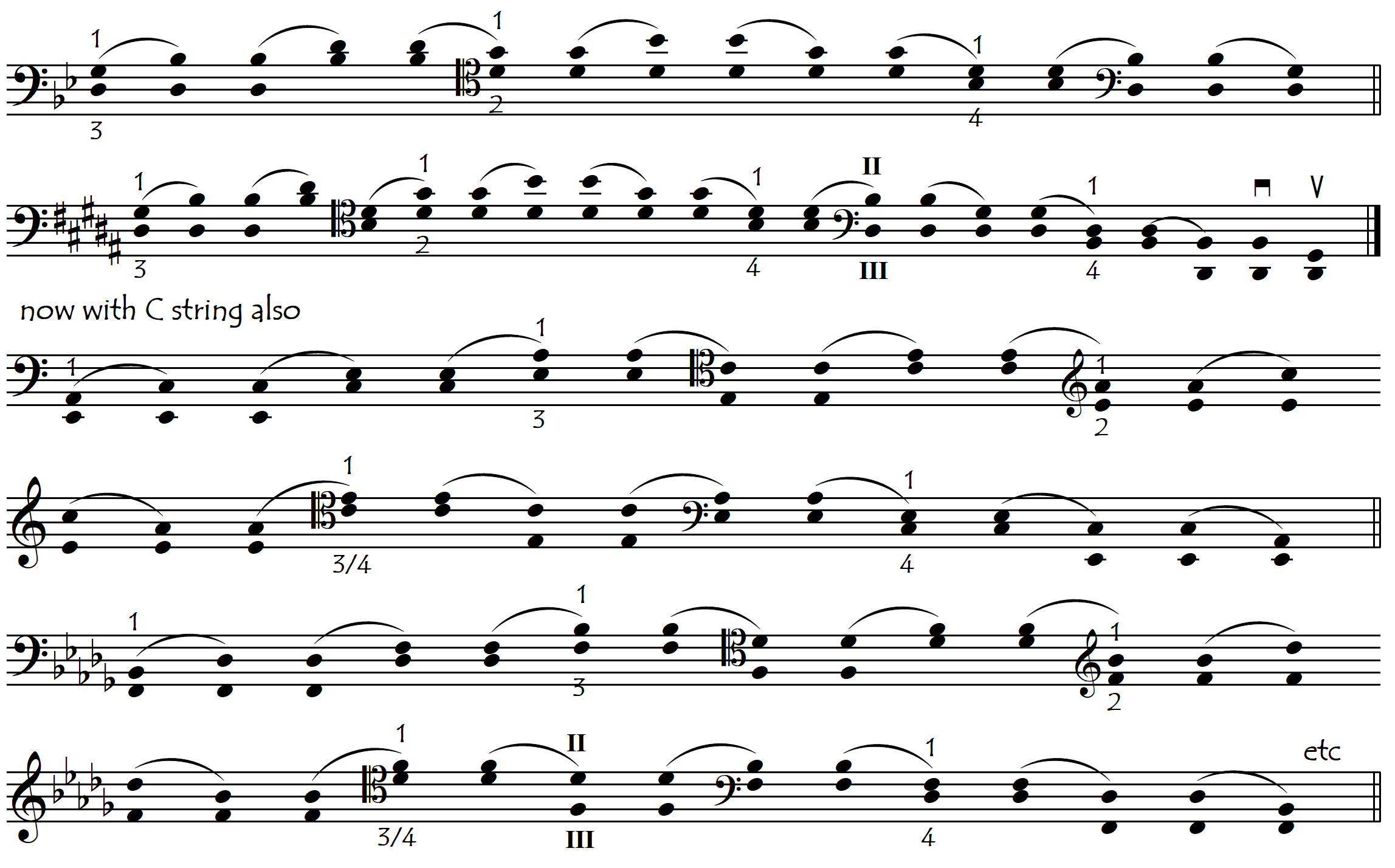

Each arpeggio sequence has its own unique finger choreography and intervals. All of them can be written out in their briefest essence as a “cell” which contains all the information we need to be able to transpose them both up and down the fingerboard, extending the arpeggio’s range ultimately to include the entire cello register from the low C-string to the high A-string. Here below is one of these possible doublestopped arpeggio “cells”:

For any basic arpeggio sequences, we can create a series of exercises that take us gradually along a progression of difficulty. The first and easiest stage is the “rolling arpeggio” model in which each shift is played on a slur in order to allow us to easily hear the glissandos. If we start on the notes which allow us to use the lowest possible position on the higher strings then we can transpose our sequence up by a semitone on each repetition.

In some of the arpeggio sequences, as we get higher, we can eventually also add the lower octaves of the arpeggio. In other words, even though we start with a one or two-octave arpeggio, we can gradually extend its range both upwards and downwards, passing to 3-octave and then ultimately to 4-octave (or more) arpeggios as shown in the following example:

Below are a selection of these doublestopped arpeggio exercises, written out in their easiest “rolling doublestop” version. To make these exercises more difficult, instead of repeating each doublestop twice and slurring it to the next one (the “rolling version”), we can play them with only one bow stroke for each doublestop. This makes the glissandos much less audible and thus the shifts become more difficult to control. The exercises can also be played as broken doublestops, with many different bowing and articulation variations in which case they become excellent string-crossing exercises also.

Doublestopped Arpeggios: No Extns and No Thumb: Hand Moves Minor or Major 3rd

Doublestopped Arpeggios: No Extns and No Thumb: Hand Moves 4th

Doublestopped Arpeggios: With Shifts On Thumb: Hand Moves 4th

Doublestopped Arpeggios: With Shifts To and From Thumb: Hand Moves 5th

Doublestopped Arpeggios: Always Extended: No Thumb: Hand Moves 4th

The ultimate test of our skill level is always the repertoire, where, as usual, we will find all sorts of unimagined combinations of problems. After all our preparatory work with the above exercises, when we go back and play the repertoire compilations on the “Doublestops” main page we should (hopefully) find the passages easier !